Click to see the full-size image

Written for South Front by Daniel Edgar

Over the course of the last few months the appointment of the next Prosecutor General became one of the most, if not the most, important of the multiple battlegrounds in the internecine factional war for control over specific State powers, functions and resources (the most important of which in this instance being the power to conduct – or to not conduct – investigations into allegations of criminal activities).

The constitutional term of the last Prosecutor General (Francisco Barbosa) expired in mid-February, and it was the responsibility of the Supreme Court to select his successor from a list of three candidates nominated by the Colombian President, Gustavo Petro. They failed to do so within the prescribed time limit, meaning that Barbosa’s former deputy (Martha Mancera) became the interim head of the agency by default, despite the fact that she has become embroiled in a rapidly accumulating series of deeply disturbing accusations and scandals alleging that she has been one of the ringleaders of a host of illegal schemes and activities that have made use of the agency’s extensive powers to block criminal investigations and destroy or manipulate evidence related to numerous major cases involving corruption, drug-trafficking, homicide, among others.

As the allegations and evidence continued to mount against the acting Prosecutor General, the magistrates of the Supreme Court added to the rapidly intensifying constitutional and political crisis by delaying and obfuscating the voting procedure on numerous occasions. Although they finally reached a decision on the constitutional successor in the plenary session held on the 12th of March, the next Prosecutor General faces a daunting task, with a long list of complicated and controversial criminal investigations pending – including numerous cases involving former or current senior executives, investigators and prosecutors within the agency itself.

Introduction

The magistrates of the Colombian Supreme Court were constitutionally bound to select the next Prosecutor General on or before the 12th of February, from a list of three candidates nominated by the sitting President (Gustavo Petro). For the first time in the history of the appointment process (created by the revised national Constitution promulgated in 1991), the list of nominees contained three eminently qualified and experienced professionals in criminal law and the conduct of complex criminal investigations whose integrity and competence cannot seriously be disputed (usually the list is made up of mostly if not entirely of political hacks and lawyers closely tied to the country’s most powerful political factions and oligarchs).

Notwithstanding the high caliber of the nominees and the expiry of the deadline, the magistrates failed to decide who will be the next Prosecutor General. Indeed, in the first two sessions held to decide the matter, many of the magistrates didn’t register a valid vote. One of the sitting magistrates (Gerardo Botero) had even lodged a formal complaint claiming that the list was invalid, notwithstanding that it had been formally accepted by the Supreme Court (mainly on the grounds that the list was discriminatory as no males were included – fortunately, upon appeal to the Council of State the petition was summarily rejected).

Beyond the office politics and apparent apathy of many of the magistrates within the Supreme Court itself, complemented by a series of schemes and manoeuvres of stigmatization and obstruction waged by powerful political factions and other vested interest groups to delay and if possible abort the selection process, by late February it seemed that a final decision could be close (in the plenary session held on the 22nd of February, the leading candidate – Amelia Pérez – received 13 of the 16 votes that are required), and the country’s most powerful organised crime families and conglomerations appeared to be getting desperate.

Their efforts to discredit and disqualify Pérez included resorting to claims that some twits posted by her husband over the last couple of years should render her ineligible, as well as lodging legal complaints against said spouse based on the twits so that they could then argue that it would be a clear conflict of interest for Pérez to be appointed while there are legal proceedings pending against her husband.

The orchestrated political, legal and media smear campaign against Amelia Pérez appears to have worked, as in the voting session held on the 7th of March she only secured nine votes, while a candidate who secured three votes in the previous vote received thirteen (Luz Adriana Camargo).

Meanwhile, as they were increasingly becoming the object of enormous political and media pressure to make a decision, the magistrates finally began to give due attention to resolving the matter and scheduled an extraordinary plenary session for the 12th of March. Amidst more drama and polemics (among other developments, Amelia Pérez announced that she was withdrawing her candidacy just minutes before the magistrates were scheduled to meet due to the stress caused by the intense media and political smear campaign against herself and her family), the magistrates finally reached a decision (with Luz Adriana Camargo receiving eighteen votes), and the formalities of swearing in the new Prosecutor General were completed ten days later.

The gravity of the prolonged stalemate over the selection of the Prosecutor General was further exacerbated by the fact that some of the allegations of criminal conduct that have been made against the interim Prosecutor General (Martha Mancera) are extraordinary (in one instance involving the murder of an undercover agent just after he had submitted a report identifying a corruption ring apparently headed by the regional director of the agency’s technical unit in Buenaventura).

Meanwhile, numerous key witnesses in other high profile cases that have been the subject of criminal investigations conducted by the Prosecutor General’s office over the last few years have also died in mysterious circumstances (most notably, one case involving former president Alvaro Uribe, and another involving a massive corruption scheme organized by the financial conglomerates Grupo Aval and Odebrecht). Taken together, the long list of accusations relating to a wide range of different illegal activities (including the obstruction or manipulation of numerous high profile criminal investigations) suggest that numerous functions and key investigative units within the office may have been thoroughly infiltrated by criminal elements at the highest levels.

While the tempest has abated for the moment following the swearing in of the new Prosecutor General, there is no room for doubt that the efforts to influence the investigation – and noninvestigation – of controversial criminal cases involving Establishment heavyweights will continue in other domains and by other means, and the new Prosecutor General will need all of her resolve and skill, as well as unwavering support from her colleagues and other State institutions, if she is to have the slightest possibility of making headway in the many daunting tasks that await her.

A long history of fierce battles among political and economic elites for appointments

An earlier report covering ongoing political developments in Colombia completed in late October of last year (Situation Report: Political Developments in Colombia – Part I) provided a brief overview of some of the prolonged and intense squabbles that have broken out among the country’s most powerful political, economic, media and organized crime groups and networks in order to secure control over the immense powers and resources of key State institutions (and the independent accountability agencies in particular, foremost of which are the Offices of the Prosecutor General, Inspector General and Auditor General).

In Colombia, the Office of the Prosecutor General is, in effect, the lead agency responsible for the conduct of criminal investigations and related legal proceedings (basically the equivalent of the Attorney General or the Director of Public Prosecutions in many other countries). While there is considerable diversity in terms of the institutional arrangements in different countries and jurisdictions providing for the establishment of the office and its relations with other branches and agencies within the system of government, it is often located in the Executive branch, notwithstanding that its functions require complete autonomy and impartiality, and that the agency must cooperate closely with other law enforcement, security and intelligence agencies as well as with the judicial branch.

When the armed conflict intensified in Colombia, administrative responsibility for the agency responsible for the conduct of most criminal investigations was transferred from the overall jurisdiction of the Executive branch (subject to direction by the Attorney General or Minister of Justice) to the public security forces (the national police or the military, depending on the nature of the alleged criminal activity to be investigated). However, it soon became apparent that the new arrangements had created a new set of problems (as many allegations of criminal conduct by members of the security forces were routinely ignored or covered up), and when the new Constitution was drafted it attempted to resolve the dilemma of ensuring independence and impartiality by placing the newly created Office of the Prosecutor General within the Judicial branch.

Nonetheless, the appointment of the director of the agency remains extremely problematic for, as argued in previous reports, rather than removing the procedure from the influence of powerful political factions and other vested interest groups and guaranteeing that the decision is based entirely on the merit and experience of the respective candidates (to the extent that this is possible at least), the appointment procedure is still very much subject to the vicissitudes of the most powerful political factions of the day. In this respect, the final report of the detailed investigation conducted by the Grupo de Memoria Histórica into the armed conflict (“¡BASTA YA! Colombia: Memorias de Guerra y Dignidad”) states:

“(Instances of undue influence in the appointment process have been made possible) by the very structure of the Office of the Prosecutor General, which has been the object of strong criticism since its creation. In effect, the fact that it is the President who nominates the candidates for the Prosecutor General has generated constant suspicions, and at times very grave suspicions, about the independence of the official. Moreover, given that the Prosecutor General (and even more so since the reform introduced by Legislative Act No. 3 of 2002) can ‘not just discretionally assign (and reassign) officials to different cases, but can also determine the juridical position that the officials must adopt in the conduct of the investigation’, the definition and conduct of all criminal investigations can be subjected to the criteria established by the Prosecutor General…”

Thus, apart from the vast financial and human resources at the disposal of the director and other senior executives and administrators, which can be used in part at least (and by no means an inconsiderable part) to repay political favours and recruit, promote or contract associates and experts of proven personal or partisan loyalty, at stake are the formidable powers and resources of the office related to the investigation of major cases of corruption, abuse of power and other criminal activities (which can also provide opportunities to not investigate criminal activities and destroy or manipulate related evidence, or alternatively to fabricate evidence against political enemies or opponents).

Recent developments in the management of the Prosecutor General’s office

In terms of the recently concluded appointment process, while some mass media outlets had been diligently attempting to whip up a scandal over some basically inane twits posted by the at the time leading candidate’s husband (some of which commented favourably on some of the sitting President’s policies and criticized some of his opponents), they have been much more diligent in terms of ignoring or downplaying the flagrant politicization of the Prosecutor General’s office by the recently retired former director (Francisco Barbosa) and deputy director (Martha Mancera – who as noted above took over as interim director on the 13th of February given the failure of the Supreme Court to designate Barbosa’s successor).

Francisco Barbosa is described in a profile report by Spanish media outlet El País (“Francisco Barbosa – El camaleón”, 12 February 2024) as one of former president Ivan Duque’s closest friends while they were at university (it was Duque who nominated Barbosa for the post, notwithstanding his lack of relevant credentials and experience).

Barbosa has been obsessed with discrediting and seeking some way to oust sitting President Gustavo Petro ever since the latter assumed office in 2022, using the office’s sweeping powers to initiate a multitude of investigations against Petro’s family and closest political allies and holding regular press conferences in order to hurl a constant stream of criticism, insults and unsubstantiated insinuations against the President.

At the same time, on numerous occasions Barbosa has either refused to open or has attempted to summarily terminate criminal investigations against some of his closest colleagues and associates – for example, the ‘ñeñepolítica’ scandal concerning evidence that his patron’s (former president Ivan Duque) political campaign received substantial financial contributions and other forms of active support and assistance from a notorious drug trafficker, while the courts have so far denied at least three formal requests by the Prosecutor General’s office over the last couple of years to terminate an investigation against former president Alvaro Uribe (Duque’s patron) for a supposed lack of evidence.

Barbosa spent much of his last week in office in the US, presumably seeking advice and assistance as to how he could disrupt and if possible nullify the appointment of his successor and prevent a genuine transfer of power from occurring that could upset the status quo (the probable motives and objectives of which are explained in more detail below), before delivering a perfunctory half-hour address to the Supreme Court at the end of the week on his activities and achievements over the last year. With respect to his efforts to prevent the appointment of his successor, he spent his last few months in office making hyperbolic media statements claiming that the entire appointment process is invalid and that his deputy should take over instead – notwithstanding that this would be a flagrant breach of the Constitution, and that he never offered any evidence to support his accusation that the selection process was fundamentally flawed.

While Barbosa’s regular media spectacles and tirades against Petro and the candidates nominated by the President to be the next Prosecutor General were widely covered in the press, most of the regular mainstream media has been downplaying or studiously ignoring a long succession of major irregularities and dysfunctions in the conduct of some of the most important criminal investigations and proceedings currently subject to the office’s jurisdiction: literally thousands of formal proceedings and investigations involving major criminal and corruption cases have been stagnating for many years, while there has been steadily mounting evidence of major irregularities and criminal activities within the Prosecutor General’s office itself.

In this respect, it appears that one of Barbosa’s key accomplices in the obstruction of criminal investigations involving powerful Establishment figures as well as in the legal persecution and political vendetta against President Gustavo Petro has been Daniel Hernandez, some of whose main accomplishments over almost twenty years working at the Prosecutor General’s office are described in an article published by Colombia Reports (“Is Daniel Hernandez Colombia’s most corrupt prosecutor in history?”, 28 July 2020).

They include allegations from his colleagues as well as from other accountability agencies (the offices of the Inspector General and Auditor General) that he has routinely engaged in illegal wiretapping operations and actively participated in the cover up of a succession of major corruption cases and political scandals involving some of Colombia’s most powerful politicians, bureaucrats and companies (including a huge embezzlement scheme by Saludcoop, the Grupo Aval/ Odebrecht corruption scandal, and the ‘ñenepolítica’ political scandal), none of which have been the subject of a conclusive investigation.

According to other media reports, Hernandez was also one of the leading figures responsible for managing the Prosecutor General’s office’s activities directed at impeding the investigation of the ‘Toga Cartel’, a crime ring that operated between 2010 and 2017 (as far as it has been possible to verify up to now). This particular white collar criminal syndicate was headed by the president of the Supreme Court and included at least one other Supreme Court magistrate, as well as numerous senior law enforcement and anti-corruption investigators and lawyers, whose members demanded massive bribes from members of Congress, provincial governors and others who were the subject of ongoing criminal investigations in exchange for bringing the respective proceedings to a speedy and inconclusive end.

The Deputy

Given the course of recent developments, however, it appears that Barbosa’s deputy (and until recently the acting director of the Prosecutor General’s office), Martha Janeth Mancera, may have become the main ring-leader of ongoing efforts by criminal elements within the agency to obstruct and derail the investigations into some of Colombia’s most important corruption and organized crime cases. While numerous allegations of gross misconduct and involvement in criminal activities have been made against her for some time (at least since 2016, when she was accused of misappropriating and selling a large quantity of cocaine that had been impounded and supposedly destroyed), over the course of the last few months Mancera has been the subject of a series of extraordinary allegations, covered in most detail by several reports produced by Colombian investigative journalism periodical Revista RAYA.

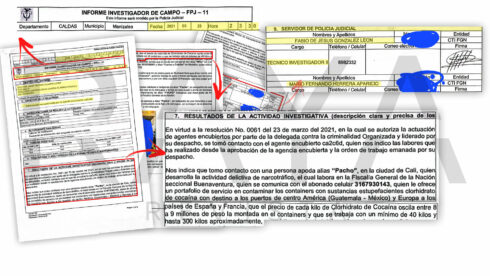

Among many other allegations of misconduct and complicity in criminal activities (some of which appear to be substantiated by detailed information, evidence and testimony from a wide variety of sources – including in several instances prosecutors and investigators from the Prosecutor General’s office with direct knowledge of the cases involved), the most astounding and disturbing accusations are related to the efforts of a team of three undercover investigators employed by the Prosecutor General’s office to get their superiors to launch a full-scale investigation into an organized crime ring they discovered in Buenaventura that was, according to a preliminary report they filed, headed by the local director of the Prosecutor General’s office in the city. One of the most detailed investigative reports describing the incident (“Vicefiscal Marta Mancera sí encubre a directive del CTI señalado de narco y estas son las pruebas”, 3 February 2024) commences:

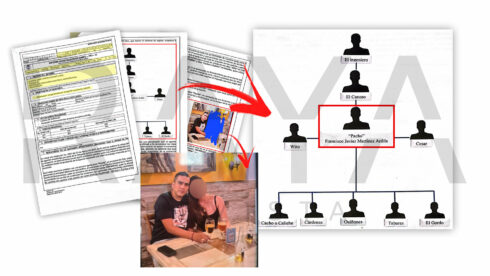

“Two days before his assassination, Mario Fernando Herrera Aparicio had prepared a detailed report for the Office of the Prosecutor General about his last mission as an undercover agent. According to the document, revealed to Revista RAYA, the director of the Technical Investigation Unit (Cuerpo Técnico de Investigación, CTI) of Buenaventura, Francisco Javier Martínez Ardila, is alias ‘Pacho’ or ‘Pacho Malo’. The undercover agent, who had been tracking Pacho’s movements since February of 2021, reported that Pacho was in charge of ‘contaminating’ cargo ships in the Pacific port with cocaine packages (of between 40 and 300 kilos, approximately) destined for Central America, Guatemala, Mexico and, in Europe, Spain and France…”

According to the report, Mario Herrera was killed in an ambush in the Cauca region (apparently by members of the ‘FARC dissident group EMC’) after being reassigned to another case within days of delivering the report on the crime ring in Buenaventura. The other two undercover investigators of the team sent to Buenaventura (Fabio Gonzalez and Pablo Bolaños) miraculously managed to escape the ambush in Cauca (they were also redeployed to the new assignment), but were themselves subsequently subjected to a full-fledged criminal investigation orchestrated by some of their colleagues at the Prosecutor General’s office after they refused to retract or modify their report on the organized crime ring in Buenaventura (an insistent request that, according to their statements – which are supported by audio recordings and other evidence – was ordered by the vice director personally). Shortly after Mario Herrera’s death, the two surviving members of the team of undercover investigators sent to Buenaventura had a personal meeting with Francisco Barbosa and Martha Mancera to discuss the findings of their investigation. According to the report published by Revista RAYA:

“All of the information (about the crime ring operating in Buenaventura) was reported on the 25th of March of 2021 to Prosecutor 51 of the Special Directorate against Drug Trafficking, Jaime Hernan Ocampo Lopez… That same night the three undercover agents (Mario Herrera, Fabio Gonzalez and Pablo Bolaños) travelled from Cali to the north of Cauca, as they were scheduled to conduct another mission involving the infiltration of a criminal gang dedicated to marijuana and cocaine trafficking…

(While they were travelling towards their destination they passed through a military checkpoint; however, several kilometres further down the road they were intercepted by a group of around seven heavily armed men on whose clothing were insignia of the ‘Estado Mayor Central’, one of the Farc dissident groups. Mario Herrera was captured and subsequently executed, however the other two agents managed to escape and ultimately sought refuge in the police station at Corinto, in northern Cauca, where they remained until the 27th of March when they were escorted to Cali by a heavy security escort…)

The following day, the 28th of March, Gonzalez and Bolaños met with the Prosecutor General of the Nation, Francisco Barbosa, and with the deputy director, Marta Janeth Mancera. That is what happened, proof of which is an audio recording (made by the two agents) revealed by Revista RAYA, on which one can hear the voices of the two most important directors of the Prosecutor General’s office…

The greeting by prosecutor general Barbosa was effusive, emotional and promised the total support of the agency for the operation the investigators were conducting… Then, deputy prosecutor general Mancera spoke, interrogating the two agents about all of the investigative processes they had conducted and seeking every detail concerning the activities that they had realized up to that time (and the evidence that they had discovered) …

According to the testimony of the two undercover investigators, Fabio Gonzalez and Pablo Bolaños, they told deputy prosecutor general Mancera during that meeting in Cali about their findings concerning the CTI official in Buenaventura. However, she showed surprise when they showed her the photo of alias ‘Pacho Malo’. One of the agents stated of what happened next: “I showed her the photo of ‘Pacho’ … and at that moment she looked as if she had seen the devil. Then she said – ‘What are you telling us? We’ll see you tomorrow’.”

Mancera never sought more information about the case… Instead, what followed was the initiation of a campaign of persecution against the two undercover agents who shortly afterwards were accused of stealing drugs that had been confiscated from drug traffickers. Mancera appointed prosecutor Daniel Hernandez to open a formal investigation based on an anonymous tip that the agency supposedly received on the 30th of March…

The aforementioned denunciation and a subsequent interview with the supposedly anonymous source (of the denunciation against the two undercover agents) were received by an official sent by deputy prosecutor Mancera to investigate the matter… That official was the head of a regional office of the Judicial Police, Victor Forero, a senior official who also happens to be very close to Mancera… He is also the investigator who was assigned to conduct the ongoing criminal case against President Gustavo Petro’s son…

(From that time on Prosecutor 51, Jaime Ocampo, was pressured by his superiors to close the undercover operation against the crime ring in Buenaventura, and eventually it was duly terminated and the undercover agents’ report redacted to remove any reference to the key suspects…)

The rest of the story leads to impunity. The undercover agents Fabio Gonzalez and Pablo Bolaños, together with the prosecutor Jaime Ocampo, ended up being processed, prosecuted and jailed through criminal proceedings directed by the aforementioned Daniel Hernandez (the same prosecutor who aided and abetted the escape of two senior Brazilian executives in the midst of the Odebrecht scandal). However, a judge subsequently freed the agents due to a lack of evidence.”

Another media report surmised of recent developments related to the case (El País, 8 February 2024, “Las Sombras de Martha Mancera, la próxima fiscal encargada”):

Mancera has been accused of covering up evidence for several years in order to protect Francisco Javier Martinez, the former director of the CTI unit in Buenaventura who has been linked to criminal organizations involved in drug and arms trafficking.

Francisco Javier Martínez Adrila, alias “Pacho Malo”, former director of the CTI in Buenaventura accused of working with drug traffickers.

Several investigations carried out by national media outlets have revealed that Mancera lied to the public when she said that there was no official document denouncing Martinez’ links with cocaine trafficking. On Saturday the periodical Raya published the document that according to Mancera doesn’t exist. With this evidence and with the testimony of the undercover agents attached to the Prosecutor General’s office who investigated Martinez’ relations with the drug cartels, the shadows of doubt remain as to whether the deputy prosecutor general knew about the findings contained in the report implicating her subordinate in criminal activities but decided not to order a detailed investigation…

An official investigation that was being conducted by a team of investigators from the CTI into the allegations made against Martha Mancera concerning the case in Buenaventura was declared closed in mid-February of this year, claiming a lack of credible evidence. However, among other recent developments, the former CTI director in Buenaventura (Francisco Martinez, alias ‘Pacho Malo’) was captured on the 22nd of February, following which a formal petition to investigate the case was finally registered with the Commission of Investigation and Accusation (Comisión de Investigación y Acusación, comprising sixteen members of the House of Representatives of the National Congress), the entity designated by the Constitution to hear accusations of misconduct or criminal activity involving senior officials of the Prosecutor General’s office.

The petition was lodged by Maria Jose Pizarro (vice president of the Senate) demanding a formal investigation of both Mancera and Barbosa for their alleged role in destroying or covering up evidence and obstructing the criminal investigation in order to protect the CTI officials in Buenaventura (among others) who had been accused of corruption and participating in a drug trafficking ring. In a media statement Maria Pizarro further argued that the proceedings should also investigate other cases in which Mancera has been accused of misconduct or of being involved in criminal activities.

Other outstanding cases and investigations

There is a long list of such unresolved cases, several of which have been the subject of investigations conducted by Mancera’s subordinates in the Prosecutor General’s office which appear to have been perfunctory and superficial at best. In this respect, a crucial aspect that remains to be determined is how many of these outstanding cases and inconclusive in-house investigations the Commission will decide to review in formal proceedings (assuming they accept the petition, which given the amount of information that has already found its way into the public domain and the gravity of the charges involved the members of the commission would find it very difficult to reject without creating another severe institutional crisis). As noted above, the accusations against Mancera of criminal conduct go back to at least 2016. Most are related to events that took place in the Valle de Cauca province, where Mancera worked in the regional headquarters of the Prosecutor General’s office (based in Cali) for many years.

One of the most prominent of the older cases is persistent allegations that she was personally involved in obstructing an investigation into the criminal activities and networks of two ‘Narcofiscales’ based in the Cali office (who are still the subject of ongoing criminal investigations into their alleged ties with local mafia groups). The two prosecutors involved have been accused not only of acts of corruption and of refusing to open investigations into local criminal syndicates, but of obstructing other investigations that had already commenced, threatening witnesses, and instigating criminal proceedings against innocent people who had made denunciations against the criminal syndicates involved. Meanwhile, in September of 2023 it was discovered that around a dozen key documents related to the investigation had disappeared (including reports by the judicial police, records from searches and inspections of premises, and other key declarations and official reports covering specific aspects of the case).

More generally, such activities would be consistent with the incremental revelations that have accompanied developments such as the investigation and prosecution of the ‘Toga Cartel’ (a crime syndicate – in effect a white collar extortion/ protection racket – headed by the president of the Supreme Court), which taken together suggest the existence of a common strategic framework and modus operandi comprising a core set of tactics and methods that can be selectively adapted and applied by their protagonists to specific contexts and cases, some of the key components of which are described in a report by the Truth Commission:

The officials involved in the Toga Cartel manipulated criminal investigations and obstructed related judicial procedures, obtained and utilized privileged information, delayed or interrupted stages in the proceedings, altered evidence and raised doubts about the credibility of witnesses through leaks to the mass media. All this in order to favour those who paid for their ‘services’ and to obtain favourable judicial decisions which appeared to be legal…

The extensive list of alternative tactics and measures that might be utilised in any given instance includes, for example: delaying, interrupting and deliberately mishandling criminal investigations and legal proceedings against associates or people willing to pay massive bribes; ‘losing’ evidence, failing to follow up on leads and gather evidence in the first place; casting doubt on and summarily dismissing unfavourable evidence or testimony while emphasizing or inventing favourable evidence and testimony; discrediting, stigmatizing and threatening witnesses who have testified against the people protected by the extortion racket, as well as opening criminal proceedings based on false accusations and evidence against such witnesses if they refuse to retract their statements.

Several of the as yet uninvestigated or unresolved accusations and cases involving Mancera have been covered in detail by Revista RAYA and other media outlets. (For example: “Las pruebas perdidas contra los ‘narcofiscales’ que rodean v la vicefiscal Mancera”, 3 December 2023; “Diego Rafael Patiño, el oscuro empresario aliado del narco ‘anestasia’ y protegido por la Fiscalía de Barbosa”, 14 January 2024; see also, for example, Colombia Reports, “Colombia’s prosecution cornered over drug links”, 16 May 2023, a report which includes links to several other outstanding cases; Infobae, 9 February 2024, “Cuáles son los escándalos en los que ha estado envuelta Martha Mancera, la nueva fiscal general encargada”; Infobae, 5 December 2023, “Fiscalía archivó indagación contra Martha Mancera: conozca los detalles”).

Recent and ongoing developments

The Commission of Investigation and Accusation has not yet made a formal statement on whether it will investigate the charges. More generally, while one could question the appropriateness of the proceedings being presided over by a group of politicians, some of whom are relatively young and have no legal training or experience at all (apart from the fact that they are generally subject to partisan allegiances and obligations – it is a reasonably safe bet that if an official investigation is opened the findings will be determined mostly along party lines), at least the formal proceedings might finally provide an opportunity for the available evidence to be presented and verified or refuted (to some extent at least) in an official forum.

The official role of the Commission is to conduct a detailed examination of the situation and determine whether the evidence suggests that the official(s) involved is guilty of misconduct. If they decide that this is the case, they must then forward a proposal to the House of Representatives noting that the charges are credible and warrant further investigation. If the proposal is accepted, the official subject to the accusation is suspended while the case is forwarded to the Senate for a ‘political judgment’ (juicio político), in which the Senate must determine whether the official is guilty of misconduct and should be dismissed or subject to other disciplinary measures. If it is determined that the official is guilty of criminal conduct, the case is forwarded to the Supreme Court for determination.

In this context, it is submitted that there is clearly sufficient evidence to establish reasonable cause for the initiation of a formal criminal investigation, and that one of the most important factors is that the proceedings must be transparent and that all of the evidence is presented with full opportunity for cross-examination, rebuttal and further investigations to be conducted as necessary. However, of equal importance is that the process of gathering, sorting, verifying and following up on all relevant evidence and testimony in the first place is conducted in such a manner that it can be guaranteed that all relevant material is included and that there is no possibility of individual investigators, their superiors, or anyone else intervening in order to ignore, fail to investigate, ‘disappear’, alter or otherwise manipulate the collection, analysis and presentation of the evidence and related information in the formal proceedings.

Evolving plots to control the office – a new ghost in the machine?

Despite the piling up of a series of extremely grave and disturbing allegations against her and some of her closest colleagues, some of which have been substantiated by considerable amounts of information and evidence deriving from a wide variety of situations, sources and witness testimony, Martha Mancera categorically rejected suggestions that she should step down as interim director of the agency. A recent media report reviewing key developments related to the main unresolved cases in which Mancera has been implicated (El País, 8 February 2024, “Las Sombras de Martha Mancera, la próxima fiscal encargada”) comments upon some of the broader consequences and ramifications of the prolonged stalemate (Mancera remained in the post until the new Prosecutor General was formally sworn in on the 22nd of March):

Another consequence of the Court not selecting the next Prosecutor General before the expiry date is that the post of deputy prosecutor general will be occupied by Gabriel Jaimes, currently the coordinator of delegated prosecutors before the Supreme Court (generally such prosecutors are assigned to conduct the most important, complicated or controversial criminal investigations).

Jaimes was also the first prosecutor assigned to conduct the investigation against former president Álvaro Uribe Vélez for procuring false witness testimony, in which he shortly thereafter requested that the court formally close the case for a supposed lack of credible evidence, a request that the courts had already denied on two occasions after concluding that the prosecutors assigned to the case had not conducted a thorough investigation.

(In this instance the prosecutors were forced to investigate as a preliminary investigation had already been conducted by a magistrate of the Supreme Court and the magistrate concluded that there was indeed credible evidence that Uribe was guilty of the charge – at the time the investigation commenced Uribe was a senator which meant that the investigation had to be conducted by the Supreme Court, but he resigned in a successful attempt to transfer the conduct of the investigation against him from the Supreme Court to the Prosecutor General’s office.)

(Apart from the mounting suspicions concerning their active involvement in numerous grave acts of misconduct), in the opinion of lawyer and professor Ramiro Bejarano, in their time at the Prosecutor General’s office both Martha Mancera and Gabriel Jaimes have demonstrated a political militancy pursuant to which they have selectively exercised their powers over the application of the criminal code in order to protect and exonerate their friends, while at the same time pursuing and persecuting their critics and enemies…

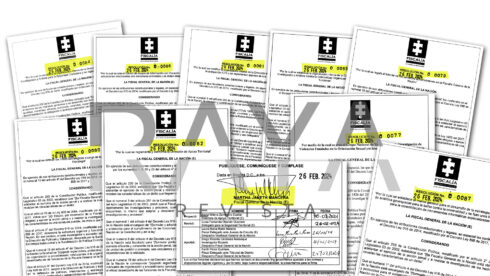

Meanwhile, it appears that the interim director made the most of her expanded powers in order to initiate or consolidate a variety of ongoing plots and schemes aimed at ensuring that her confidantes and accomplices keep control over key powers and functions after the next Prosecutor General is sworn into office. The most brazen and elaborate of these schemes was recently examined in a joint investigation by Fundación Paz y Reconciliación and Revista Raya (“Mancera reestructuró la Fiscalía antes de que la Corte Suprema elija nueva Fiscal General”).

According to the report, on the 26th of February Mancera issued a flurry of nine resolutions ordering a series of major structural and operational alterations related to the agency’s internal administrative arrangements as well as its relations with other agencies (including the judicial police and other criminal investigation units, the Inspector General, and specialized units responsible for security and protection schemes, among many others). The primary objective of the resolutions is to transfer most of the Prosecutor General’s key legal and administrative functions and powers to the deputy, while at the same time creating a network of parallel administrative structures and work groups within the agency whose members will be selected by and report directly to the deputy instead of to the Prosecutor General.

MORE ON THE TOPIC:

amerikunt–we are most corrupt immoral scum on earth

remove all 8 americiunt military bases in colombia and elect more russian mayors

nobody gives a fuck about us beaners. it’s so sad. we want attention!!! we are so pathetic 😢

well it seems that southfront is quite interested in colombia but not a word about the dictatorships of cuba and venezuela where people are dying of hunger