Written by Daniel Edgar exclusively for SouthFront

The objective of the study is to provide an integrated or multiple-perspective overview of the fundamental changes that have occurred in a selection of national and international financial systems and markets, and of how recent trends and developments related to the extraordinary degree of market concentration that now exists in key financial sectors and the ownership of publicly-listed companies have manifested in a variety of contexts (including a comparative overview of the ownership of publicly-listed companies in the United States, Australia and Canada, and corresponding developments in several financial sectors and markets at the international level). The following is some excerpts taken from a new study – the complete report is freely available in PDF format at Independent Academia (author Daniel Edgar).

INTRODUCTION

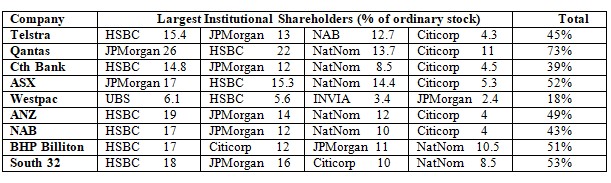

While putting together a list of the shareholders of major companies in some of the most strategic and profitable sectors of the Australian economy several years ago it soon became apparent that almost all of them are substantially or majority-owned and potentially controlled by just four financial entities: JP Morgan, Citibank, HSBC and National Nominees. The four companies also own a majority of the shares of the stock exchange itself (Australian Stock Exchange – ASX), and therefore have a privileged role in the day to day management, supervision and regulation of their playpen. The specific quantities for the companies surveyed were as follows.

TABLE 1

THE LARGEST SHAREHOLDERS OF MAJOR COMPANIES ON THE ASX

While the figures cited above are only a basic estimate, in most cases the total stake of the four core institutional investors is probably somewhat larger than the percentages cited above, dispersed through smaller holdings by other controlled entities – the figures were compiled from a list of the twenty largest shareholders of each company (hence smaller shareholdings are not included), and the estimates also do not take into account the shareholdings of other partially-controlled corporate entities.

Among the companies in which this exclusive club of foreign institutional investors between them own over 50% of the publicly-listed stock (or somewhat less in some cases, but undoubtedly a large enough stake to potentially exercise a substantial degree of control over the respective companies if they were inclined to do so) are BHP Billiton and South 32 (in the mining and energy sector), and three of the prime national assets that were privatized by the Australian government in the 1980s and 1990s (the Commonwealth Bank, the national airline Qantas, and the national telecommunications company Telstra). It was somewhat surprising that the extent of their centralized ownership, potentially enabling them to direct and control the strategic objectives and operational management of such a large proportion of the Australian economy, is so openly flaunted, in effect ‘hidden in plain sight’ (it is never mentioned in the media, parliamentary debates or the public discourse generally). Best of all, it is not even their own money: most of the billions of dollars at their disposal are the deposits and investment funds of their clients.

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE AND MINING PROJECTS IN COLOMBIA

The objective of the initial research project examining the largest shareholders of companies listed on the stock exchange was to identify the main institutional shareholders of BHP Billiton and South 32. Both companies are involved in the management of two mining projects in Colombia: BHP Billiton owns one third of the Cerrejon coal mine (together with Anglo-American and Glencore/ XStrata), while South 32 owns over 99% of the Cerro Matoso ferronickel mine and smelter complex. South 32 acquired Cerro Matoso from BHP Billiton in 2015. However, the four largest shareholders of both companies are the same and their combined stake is over 50%, so it could be argued that real ownership and control of the mining project never changed when the legal title was transferred from BHP Billiton to South 32.

Each of the massive mining projects have had devastating social and environmental impacts, and community representatives have lodged a succession of legal challenges for grave and persistent violations of their constitutional rights, including several forced displacements of entire communities, inadequate provision for the relocation of displaced communities, and denial of the rights to due process, prior informed consent, and access to water, essential services and a healthy living environment (Chomsky et al., 2007: LMN, 2009). As a result, the two mining projects have been the subject of numerous determinations by the three highest courts in Colombia (the Supreme Court, the Constitutional Court and the ‘Council of State’ – Consejo de Estado) finding the operators of the mines and the Colombian government jointly responsible for grave violations of the rights of the residents of affected communities. Relevant determinations include, in the case of Cerrejon, Sentence T-256 in 2015, Sentence T-302 in 2017, and Sentence T-415 in 2018 (all involving proceedings before the Constitutional Court) and a related judgment by the Council of State proclaimed on the 13th of October 2016, while Sentence T-733 of 2017 (determined by the Constitutional Court) involved conditions at Cerro Matoso.

On several occasions protest actions have been held at the annual general meetings of BHP Billiton in London and Melbourne (organized by civil society organizations and representatives of affected communities) to inform shareholders of conditions at the mining projects and demand decisive changes in management practices and standards. However, most of the affected communities’ grievances have not been adequately addressed, and the Colombian government together with the mine operators also have not complied with many of the court orders directing remedial action. The judicial determinations and related developments are the subject of a series of reports by the present author (Edgar, 2019). The complicated underlying structures of ownership and control of BHP Billiton and South 32 demonstrate the difficulties associated with trying to influence management decisions or hold the nominal owners of the mining projects accountable individually (there have been active international social and legal campaigns seeking to address their social and environmental impacts as well as other persistent legal violations for many years). Ultimately, the two mining companies are merely artificial legal and administrative constructs which serve as useful investment vehicles and smokescreens for the real owners and beneficiaries. From this broader systemic perspective, social campaigns demanding greater corporate accountability could potentially be more effective if they are also directed at the principal owners, superior decision-makers and main beneficiaries of the two mining companies – in this instance, JP Morgan, Citibank and HSBC.

JUST ANOTHER INTERMEDIATE LAYER OF OWNERSHIP AND CONTROL

Nonetheless, despite their extraordinary financial and economic power in Australia, it turns out that the three main corporate giants involved (JP Morgan, Citibank and HSBC) are themselves simply an intermediate level of ownership and control which are in turn owned and controlled by another very select and limited number of shareholders, principal among which are Vanguard Group, Inc., BlackRock, Inc., State Street Corporation, Fidelity Management & Research FMR LLC (hereafter Fidelity MR – the company was recently reconstituted as Fidelity Investments (FMR LLC)), and Capital Research & Management Co. (hereafter Capital RM – the company was also recently reconstituted and is now formally known as Capital Group Companies, Inc.).

Upon further investigation, it turns out that these same financial entities that own substantial stakes in JP Morgan, HSBC and Citigroup (and through them a large portion of the main Australian economic sectors) also dominate the ownership of most of the other large publicly-listed corporations in the financial sector in the United States (including many companies that are commonly considered to be financial and economic powerhouses in their own right, such as Bank of America, Wells Fargo, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley). Indeed, following the lines of ownership behind the leading companies in most of the major economic sectors listed on the stock exchange in the US or Australia almost always leads to the same five or six financial institutions (Vanguard, BlackRock, State Street Corporation, Fidelity MR, Capital RM, and T. Rowe Price Associates) being listed among the ten largest shareholders.

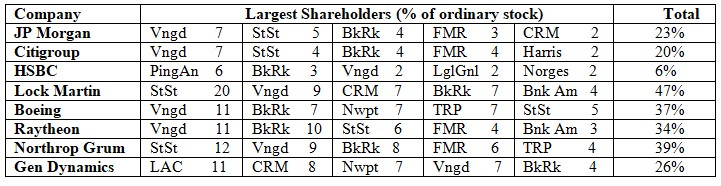

To take another example, a report analysing the political and economic power and influence of five of the largest weapons producers who have profited most from the astronomical sums spent on the open-ended ‘War on Terror’ – Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Raytheon, Northrop Grumman, and General Dynamics (Benjamin & Davies, 2018). A significant proportion of the companies’ profits have derived from privileged ‘cost-plus’, no-bid contracts with the US military, presumably facilitated to a not inconsiderable extent by their targeted lobbying and recruitment of senior Pentagon officials and their lavish funding of politicians from both major political parties in the US Congress.

However, the study misses one key detail: the same six financial entities listed above also feature very prominently among the largest institutional shareholders of all of the arms companies reviewed (see Table 2, which also includes a summary of the largest shareholders of JP Morgan, Citibank and HSBC – the latter domiciled in the United Kingdom). Indeed, Vanguard (Vngd) and BlackRock (BkRk) are at the top of the list of the largest shareholders of all five pillars of the permanent warfare complex, followed by State Street Corporation (StSt) which is among the largest five shareholders of four of the companies. Meanwhile, Capital RM (CRM), Newport Trust (Nwpt), Fidelity MR (FMR), Bank of America (BofAm), and T Rowe Price (TRP) are among the five largest shareholders of two of the arms companies.

TABLE 2

THE LARGEST SHAREHOLDERS OF FIVE MAJOR ARMS COMPANIES

The total in the final column of the table refers to the combined holding of the main financial entities reviewed in the present study (Vanguard, BlackRock, State Street, Capital RM, Fidelity MR, and T Rowe Price). As in Table 1 (and the tables in the following sections), the figures are only a basic estimate derived from the list of the ten largest institutional shareholders of ordinary stock (the total combined stake is probably larger as the above percentages also don’t include smaller stakes held by other subsidiaries or partially-controlled corporations and investment funds).

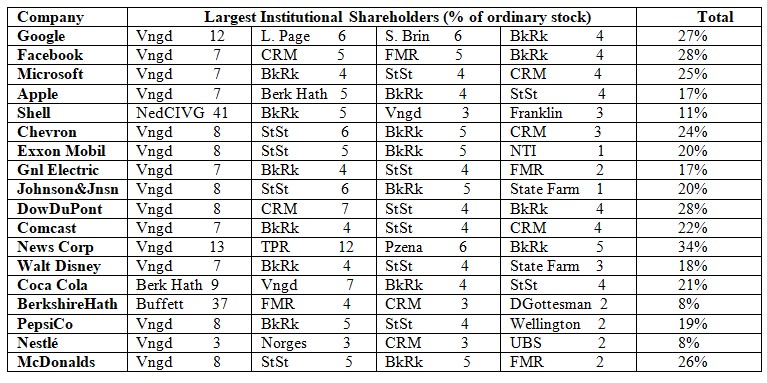

A shortlist of some of the most well-known companies that this exclusive group of financial entities (particularly BlackRock and Vanguard) has a substantial interest in provides just a small sample of their holdings, which is nonetheless sufficient to demonstrate their potential influence and control over the most strategic and lucrative markets and economic sectors of many countries around the world (either directly or indirectly). The following data (see Table 3) quantify the holdings of the four largest institutional shareholders of a selection of high profile companies, each of which has considerable assets, revenues and market power in their own right – often including supposedly fierce rivals and competitors, such as Coca Cola and PepsiCo (the data was compiled in 2018 from Marketscreener and Morningstar).

TABLE 3

THE LARGEST SHAREHOLDERS OF A SELECTION OF HIGH PROFILE COMPANIES

PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS ON THE CORE OF THE FINANCIAL SYSTEM IN THE US

Thus the short sample of firms in the preceding figure reveals the same financial institutions featuring prominently among the four largest shareholders of most of the eighteen publicly-listed companies surveyed. Specifically, Vanguard appears among the four largest shareholders of all but one (and is the largest institutional shareholder in all but three), and BlackRock appears in all but two. Between them they usually hold between 15-20% of the stock. The other most prominent firms on the list are (in descending order) State Street Corporation (twelve), Capital RM (seven) and Fidelity MR (four).

A monumental study completed by Fichtner, Heemskerk and Garcia-Bernardo in 2017 provides a wealth of comprehensive and detailed information on many crucial factors and questions concerning recent developments and related trends in financial ownership and corporate governance, focusing specifically on the ownership of publicly-listed companies in the United States (Fichtner et al., 2017). The study merits reading in its entirety by anyone interested in the functioning of the financial system, how it has been altered by the cumulative effects of three decades of deregulation and shifting investment strategies, and how this has affected corporate ownership, control and management. The principal objectives and findings of the analysis are described by the authors as follows:

“Since 2008, an unprecedented shift has occurred from active towards passive investment strategies. We showed that this passive index fund industry is dominated by BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street. Seen together, these three giant passive asset managers already constitute the largest shareholder in at least 40 percent of all U.S. listed companies and 88 percent of the S&P 500 firms. Hence, the Big Three, through their corporate governance activities, could already be seen as the new ‘de facto permanent governing board’ for over 40 percent of all U.S. listed corporations…

Together, these 1,662 American publicly listed corporations have operating revenues of about US$9.1 trillion, a current market capitalization of more than US$17 trillion, possess assets worth almost US$23.8 trillion, and employ more than 23.5 million people. When restricted to the pivotal S&P 500 stock index, the Big Three combined constitute the largest owner in 438 of the 500 most important American corporations, or roughly in 88 percent of all member firms.” (Fichtner et al., 2017, p.15)

Basic Ownership Structure and Corporate Profile of the Big Three

In terms of the overall size, basic corporate form and operational structures of the Big Three themselves, the authors note that each firm has adopted very distinct legal forms, corporate governance systems and investment strategies:

“Although the Big Three have in common that they are passive asset managers, they are quite different in their own corporate governance structures. BlackRock is the largest of the Big Three—and represents the biggest asset manager in the world. At mid-2016, BlackRock had US$4.5 trillion in assets under management. BlackRock is a publicly listed corporation… Vanguard – with US$3.6 trillion in assets under management in mid-2016 – is currently the fastest growing asset manager of the Big Three… Vanguard is mutually owned by its individual funds… State Street is slightly smaller than BlackRock and Vanguard, but still one of the largest global asset managers. In mid-2016, it had US$2.3 trillion in assets under management.” (Fichtner et al., 2017, p.8)

With respect to the main results and findings of a comprehensive analysis of the significant ownership positions of the Big Three in publicly-listed companies, in terms of both the breadth and depth of corporate ownership (the number of companies in which each firm has a significant stake, and the magnitude of that stake in each instance), BlackRock and Vanguard are an order of magnitude larger than all of their peers:

“BlackRock and Vanguard are by far the broadest global block-holders in listed corporations according to both the 3 percent and 5 percent thresholds. These block-holdings are located in a number of countries around the world; the majority, however, is in the United States… BlackRock holds 5 percent blocks in more than one-half of all listed companies in the United States. That is significantly more than five years before… Vanguard’s ownership positions also concentrate in the United States. Of the 1,855 five percent block-holdings, about 1,750 are in U.S. listed companies.” (Fichtner et al., 2017, pp.13-14)

State Street has a narrower and shallower share ownership profile or portfolio, suggesting that its owners and managers have decided to concentrate their more limited resources on a select group of companies. More generally, the overall inherent or structural power and influence available to State Street – whether through institutional mechanisms or otherwise – is also considerably less than the other two.

As the size and diversity of the three firms’ holdings has grown, each of them has developed a central governance strategy which usually determines or provides the basis for specific policies, objectives and voting positions in any given situation:

“State Street for instance highlights that they follow ‘a centralized governance and stewardship process covering all discretionary holdings across our global investment centers. This allows us to ensure we speak and act with a single voice and maximize our influence with companies by leveraging the weight of our assets’… The analysis of the voting behaviour underscores that the Big Three may be passive investors, but they are certainly not passive owners. They evidently have developed the ability to pursue a centralized voting strategy – a fundamental prerequisite to using their shareholder power effectively.” (Fichtner et al., 2017, pp.10-21)

The detailed examination of the record of voting patterns and behaviour of the Big Three demonstrates several other key features and trends related to both the existence of a highly centralized corporate governance strategy within each of the three firms, as well as the existence of a common – or at the very least a complementary or ‘like-minded’ – set of institutional objectives and interests shared by the three firms. The overall affinity of interests and attitudes of the three firms is apparent in the very similar pattern of voting positions of each of them in the shareholder meetings and proxy votes of the companies they own. Specifically, the authors state of their findings on the three firms’ voting behaviour:

“Overall, the internal agreement in proxy voting among the Big Three’s funds is remarkably high. In fact, BlackRock and Vanguard are on the forefront of asset managers with internally consistent proxy voting behaviour… The voting behaviour of BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street is similar to that of most active mutual funds: they side with management in more than 90 percent of votes. This echoes increasing concerns of various stakeholders about the lacking response of investment funds on critical corporate governance issues such as executive pay…

Perhaps most interesting are the proposals where the Big Three oppose a positive management recommendation. We found that about half of them concern the (re-) election of the board of directors… This suggests a proxy voting strategy where the Big Three typically support management, but will use their shareholder power to vote against management when they are dissatisfied.

This leads to two conclusions. First, the voting behaviour of the Big Three at AGMs is by and large management-friendly and does not reflect a highly engaged activist corporate governance policy. Second, the high propensity to vote against management (re-) elections is consistent with the idea that the Big Three use their voting power to make sure they have the ear of management. Instead of open activism, the Big Three may prefer private influence. In the words of Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock: ‘As an indexer, our only action is our voice and so we are taking a more active dialogue with our companies and are imposing more of what we think is correct’.” (Fichtner et al., 2017, pp.18-20)

In effect, it would appear that the owners and managers of this small and exclusive cluster or network of financial conglomerates located at the highest peaks of the financial system – and the economy generally – have elaborated a system of centralized governance and direction by remote control, a system that operates in a condition of ‘auto-pilot’ for the most part. The firms use their raw financial power and other forms of influence to lobby for the appointment of directors that they approve of, after which it is quite likely that those same directors will not usually act contrary to the interests or instructions of the firms that secured their appointment in the first place. And if the appointees persist in defying the advice, instructions or demands of their company’s most powerful owners, they can use their disproportionate voting power (along with their also very considerable influence through informal channels) to support a motion to reprimand or replace the directors that have not followed their instructions.

Centralized Financial Power and Corporate Governance by Remote Control

With respect to the structural and systemic implications of recent developments and trends, the authors suggest that the magnitude of the changes that have occurred undoubtedly amounts to a historic tectonic shift in the fundamental components, norms and practices underlying the functioning of the financial system and corporate governance generally. From this broader historical and institutional perspective, the authors also note that in contrast to their predecessors, the new age financial barons tend to wield their vast financial power over the economy and corporate governance through an integrated ‘network of control over listed companies’, typically relying on less visible forms of direction and control:

“(The combined holdings of the Big Three suggest that together) they occupy a position of unrivalled potential power over corporate America… (We are witnessing) a concentration of corporate ownership, not seen since the days of J.P. Morgan and J.D. Rockefeller. However, these finance capitalists of the gilded age exerted their power over corporations directly and overtly, through board memberships and interlocking directorates. This is not the case with the Big Three, (which typically rely on) more hidden forms of corporate governance.” (Fichtner et al., 2017, pp.2-17)

The authors note the unprecedented nature of the challenges and risks these developments entail in terms of key structural features and characteristics such as systemic financial risk, market competition and efficiency. Another common feature of this new age finance capitalism is that most of the available capital and investment funds are directed to taking over and controlling existing commercial and industrial assets rather than being used to create ‘greenfield investments’ in new industrial, social and economic projects. It would appear that, almost by default (or by design), the fusion of ownership and control at the core of the financial system has produced a situation where traditional fundamental concepts and principles – such as ‘free’ markets, arm’s-length trading and dealing, conflicts of interest, insider trading, the separation of ownership and management of publicly-listed companies, market efficiency and market competition, or abuse of market power – have been quietly and unobtrusively abandoned by policy makers and regulators, or that they have simply become irrelevant and obsolete.

CORPORATE STRUCTURES AND POWER AT THE CORE OF THE FINANCIAL SYSTEM

The detailed analysis discussed above concerning the respective and combined shareholdings of BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street Corporation in publicly-listed companies in the United States – and of how this structural financial power has been systematically exploited by the two largest firms in particular to supervise and influence the management of the companies that they have a significant stake in – demonstrates the extraordinary extent to which the three financial giants have come to dominate the ownership and direction of ‘corporate America’.

Nonetheless, the primary focus of that study is limited to passive investment fund managers and specifically the shareholding portfolios of ‘the Big Three’. When the respective shareholdings of other types of public and private financial institutions, companies, investment vehicles and fund managers are taken into account it is clear that several other corporations and investment funds could also be considered to constitute an integral part of the core or primary layer of financial power and corporate ownership and control – or at least a substantial and potentially very powerful secondary layer of concentrated financial power which many of those firms have also used to gain significant ownership positions in key market sectors, industries and companies.

In this sense, to gain a more complete understanding of the entire range of corporate entities and investment funds that make up the membership of this elite and privileged core or nucleus of the financial and economic systems (as it pertains to the ownership and control of publicly-listed companies in the US) it would be necessary to identify and include all of the financial giants located within or at the margins of this secondary layer. Such a list would undoubtedly include, but is by no means limited to, the companies mentioned previously – in particular Fidelity MR, Capital RM, and T Rowe Price. In this respect, the study mentions two other asset managers whose overall financial ownership positions are also noteworthy (but whose holdings and voting behaviour are not examined in detail as they are not major ‘passive investment funds’): Fidelity MR and Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA). The authors comment of these two firms:

“Fidelity is by far the largest actively managed mutual fund group… In contrast to the Big Three, Fidelity has a much narrower and deeper ownership profile; it holds roughly 700 five percent block-holdings in US corporations (the other 600 are international), and of this about 300 are ten percent blocks. DFA has a very broad and shallow ownership profile that resembles that of a passive index fund; it holds approximately 1,100 three percent holdings and 540 five percent blocks in US publicly listed companies.” (Fichtner et al., 2017, p.14)

Hence, it could be inferred that although it is smaller in size, the owners and managers of Fidelity MR have also adopted a very strategically-oriented investment and corporate management plan, while DFA has preferred a more traditional ‘passive’ investment strategy that is less oriented at gaining some degree of control or influence over the companies that they have invested in.

THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM – A HYBRID FORM OF REMOTE CONTROL?

An analysis of the largest institutional shareholders of the most influential member banks of the Federal Reserve System provides another very distinctive insight into financial power relations at the core of the system given the primordial role of ‘the Fed’ in the determination of economic policy and the regulation of the financial sector in the United States. According to a series of descriptive bulletins posted on its website: “The Federal Reserve System fulfils its public mission as an independent entity within government.” The bulletin describing the ownership structure of the Federal Reserve System goes on to assert, “It is not ‘owned’ by anyone and is not a private, profit making institution.” (FRS, 2013a) Elaborating on these enigmatic statements it states:

“The 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks, which were established by the Congress as the operating arms of the nation’s central banking system, are organized similarly to private corporations – possibly leading to some confusion about ‘ownership.’ For example, the Reserve Banks issue shares of stock to member banks. However, owning Reserve Bank stock is quite different from owning stock in a private company. The Reserve Banks are not operated for profit, and ownership of a certain amount of stock is, by law, a condition of membership in the System. The stock may not be sold, traded, or pledged as security for a loan; dividends are, by law, 6 percent per year.”

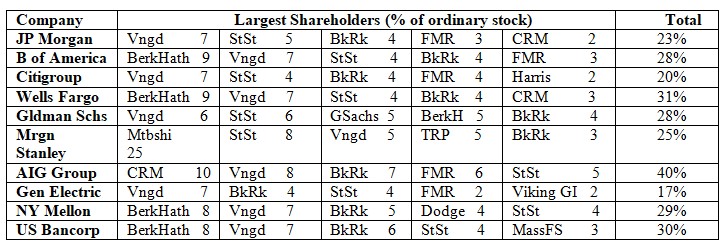

At the top of the list of the ‘Top 50 holding companies’ (as of mid-2018) of the Federal Reserve System, who would therefore also be the most influential member/ shareholders, are the same commercial banks listed in previous sections, of which Vanguard and BlackRock are – without exception – two of the largest shareholders (as are a substantial number of their partially-owned and controlled companies). Specifically, JP Morgan Chase & Co. (incorporated in New York) was the largest member/ shareholder in 2018 with approximately $2,600 billion in total assets, followed by Bank of America Corporation ($2,300bn, Charlotte NC). The third largest was Citigroup Inc. ($1,900bn, NY), then Wells Fargo & Company ($1,900bn, San Francisco CA), Goldman Sachs Group Inc. ($970bn, NY) and Morgan Stanley ($880bn, NY). The size of the next largest members falls off sharply: the seventh largest (American International Group – AIG) registered total assets of $460bn and the other three had less than $400bn (General Electric Capital Corporation, Bank of New York Mellon Corporation, and U.S. Bancorp). Table 4 lists the largest institutional shareholders of the top ten member/ shareholders (in descending order).

TABLE 4

This compilation of the five largest institutional shareholders of each of the top ten member/ shareholders of the Federal Reserve System provides further details and clues about relative and absolute structural power at the core of the financial system from a related but nonetheless very distinctive and significant perspective. Considered from this angle, the extreme concentration of raw financial power and inherent structural or systemic influence at the top is confirmed, and it may also be possible to glean further insights into the relative weighting or power of the main financial corporations and entities that are definitely within the first or second layers of the nucleus of financial ownership and control from their respective ownership stakes in the main member banks.

Perhaps most significant of all, Vanguard’s status as ‘first among equals’ – by a substantial margin – is confirmed. It is among the five largest institutional shareholders of all ten of the largest member banks of the Federal Reserve (and is the largest or second largest shareholder in all but one, in which it is third place). BlackRock and State Street are also among the five largest shareholders of all ten member banks (usually around third place in the pecking order), followed by Fidelity MR and Berkshire Hathaway (both are among the largest shareholders of five of the ten member banks – it is however noteworthy that the latter is the largest shareholder of four of them), while Capital RM is among the top shareholders of three. Between them, ‘The Big Five’ hold a total of between 17% and 40% of the stock (averaging just under 30%). The other major shareholders on the list don’t appear more than once (Goldman Sachs, Mitsubishi, Harris Associates, Viking GI, Dodge & Cox, T Rowe Price and Massachusetts Financial Services Co.).

THE SECONDARY LAYER OF FINANCIAL POWER AT THE CORE

With respect to the development of a more comprehensive and multi-dimensional evaluation of structural power in the financial and economic systems, it would be necessary to take into account the full range of financial entities, investment vehicles and corporate networks that have formed around the core of the financial system, as well as the main financial and economic sectors and markets that they are most active in. In this respect, a detailed investigation of ownership patterns and corporate governance in each major financial, industrial and economic sector could provide additional insights into the relative and absolute financial power of individual firms located at the core, as well as of how particular functions or components of the financial and economic systems have been affected by recent developments related to the concentration of financial power, corporate ownership and governance.

The other figures and lists compiled in the previous sections provide additional information and insights in this respect. The respective lists of the main shareholders of the largest arms manufacturers and other high profile publicly-listed companies (see Tables 2 and 3) are dominated by the same companies (with Vanguard, BlackRock, and State Street Corporation clearly at the centre of the core, while Fidelity MR and Capital RM appear to be located within the secondary or outer layer). The illustrative cross-section of the shareholders of the most influential members of the Federal Reserve System (see Table 4) corroborates this hypothesis, and further suggests that Berkshire Hathaway has concentrated considerable effort on this peculiar hybrid financial institution of primordial importance to the financial system and the national economy, given that it is the largest institutional investor in four of the largest member banks notwithstanding its relatively more limited resources.

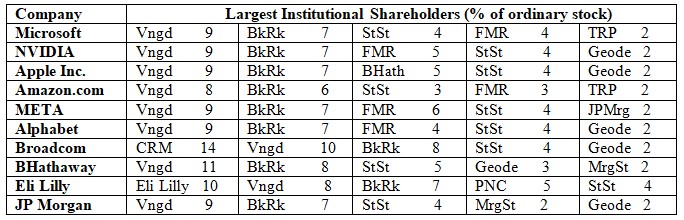

One more illustrative sample of corporate ownership at the commanding heights of the US economy will be included here in order to provide a final exploratory cross-section of financial power and corporate ownership and control (see Table 5): a survey of the main institutional shareholders of the ten largest companies (by market capitalization) listed on the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index (measured as the percentage of total ordinary shares held by each firm from data compiled in June 2024).

TABLE 5

THE LARGEST SHAREHOLDERS OF THE TOP TEN S&P 500 COMPANIES

Once again, the results are very similar to those produced in the other sample cross-sections of corporate ownership (notwithstanding a relative shift in the holdings of several of the ‘secondary layer’ firms). Vanguard’s dominant position is quite extraordinary – it is the largest institutional investor in eight of the ten companies, and is second in the other two (with most stakes around 8-9%). BlackRock’s inherent or structural financial power over the companies reviewed is also exceptional – it has the second largest holding in eight of the companies, and is third in the other two (averaging around 7-8%). State Street also features among the top five shareholders of all ten companies (usually in third or fourth place with 4-5%).

Moving on to what could be considered the transition zone between the primary and secondary levels of the central financial core, Geode Capital Management LLC has become one of the most significant players in recent years (among the top five shareholders of six of the ten companies and in the top ten of three others, usually with a stake of around 2%). Fidelity MR is one of the top five shareholders of five companies (and in the top ten of three others), T Rowe Price is next appearing among the top five shareholders of two companies and in the top ten of seven others, while Capital RM is among the top five shareholders of one company and the top ten of five others. Morgan Stanley and JP Morgan Chase are also significant (each is among the top five shareholders of one company and among the top ten shareholders of seven and six companies respectively). Other financial companies and asset managers belonging to this exclusive group of firms located within or at the margins of the central core of the increasingly integrated system of financial ownership and corporate governance that has formed over the last two or three decades would likely include Wellington Management Co. LLP, Massachusetts Financial Services Co., and Dimension Financial Advisors.

THE FINAL (VISIBLE) LAYER OF FINANCIAL OWNERSHIP AND CONTROL

So who are the owners of these financial/ corporate behemoths, what are they exactly, and how did they manage to achieve such a commanding position of control over the financial system generally and corporate ownership specifically in such a short period of time? The following section seeks an answer to these questions by reviewing the available information on the ownership, corporate structure and governance of Vanguard, BlackRock and State Street themselves. Vanguard and BlackRock are of course the two largest financial entities by a considerable margin in terms of assets under management and their ownership of publicly-listed corporations in the US. The former has developed a complicated and vaguely defined sui generis form of corporate organisation and governance which makes it especially difficult to identify a definitive final decision-making authority, structure or procedure. BlackRock and State Street are publicly-listed companies, while the two next largest institutional investors (Fidelity MR and Capital RM) are privately owned. Although BlackRock is the largest in terms of total AUM, Vanguard will be reviewed first as it has been somewhat more active in deploying those assets to acquire a strategic stake in publicly-listed companies in the US.

The Vanguard Group, Inc.

Vanguard was established in 1975 by John Bogle. Its headquarters is in Malvern (Pennsylvania), and its commercial activities include the management of exchange-traded funds, pension and mutual funds, variable and fixed annuities, and offering brokerage and financial planning services. The firm expanded rapidly during the 1980s and by the late 1990s was among the largest fund managers in the world. According to its own estimates the corporate group as a whole has a total of $8.6 trillion assets under management (second only to BlackRock), with approximately 20,000 employees and 50 million investors or clients (dispersed among 423 separately constituted investment vehicles and mutual funds worldwide, 208 of which are registered in the US).

There has been a substantial degree of continuity in the membership of the central board of directors and senior management: for example, John Bogle was Chairman until 1999 when he was replaced by John Brennan, and William McNabb was appointed CEO in 2008 followed by Tim Buckley in 2018 (who also served as Chairman and President). Salim Ramji replaced Tim Buckley as CEO in 2024, Greg Davis was appointed President, and longtime board member Mark Loughridge took over the Chairman’s position. Ramji joined Vanguard from BlackRock (!), where he was the manager of a major investment fund and a member of the global executive committee. A company profile of Vanguard by Bloomberg (2018a) describes it as ‘a privately owned investment manager’, but the underlying ownership, corporate structure and chain of command and control across the corporate group as a whole is decidedly obscure and elusive. According to the company’s own statements on its webpage:

“Vanguard set out in 1975 under a radical ownership structure that remains unique in the asset management industry. Our company is owned by its member funds, which in turn are owned by fund shareholders. With no outside owners to satisfy, we focus squarely on meeting the investment needs of our clients… Vanguard is mutually owned by its individual funds and thus ultimately by the investors in these funds. Consequently, the group does not strive to maximize profits for external shareholders but instead operates ‘at-cost’.”

Such affirmations may be useful as a form of marketing and self-promotion but they provide no real clue as to how the 50 million individual investors and clients scattered among more than 400 separate investment funds and entities could effectively participate in or influence strategic decision-making and corporate governance (which as noted previously is very centralized and strategically oriented). While it might be possible to glean some insights from official documents describing the ownership and management structures of the largest publicly listed investment vehicles and holding companies controlled by the parent company, a detailed examination of this question is beyond the scope of the present study.

BlackRock, Inc.

BlackRock also provides a wide range of investment, risk management, financial planning and advisory services for both institutional and retail clients. The company was founded in 1988 (the founders included Ralph Schlosstein, Susan Wagner, Robert Kapito and Laurence Fink), the corporate headquarters is located in New York, and it was listed on the New York Stock Exchange in 1999. The company rose from out of nowhere to become one of the largest institutional investors in the world over the next two decades, catapulted in part by its merger with Barclays Global Investors in 2009 after which it became “the world’s largest investment management company”. By the end of that same year: “assets managed on behalf of clients domiciled in the United States and Canada (including offshore investors), totaled $2.042 trillion or 61% of total AUM, an increase of $1.070 trillion”. (Blackrock, Annual Report, 2009, pp.2-10) Prior to this the firm acquired or merged with Merrill Lynch and developed similar ties with PNC Financial Services Group, Inc., which also contributed to its rapid expansion and the consolidation of its power base.

As with Vanguard, there has been a high degree of continuity in the membership of the central board of directors and senior management: Laurence Fink and Robert Kapito have been key personnel since its founding and retain the key positions of Chairman and CEO (Fink) and President (Kapito). Indeed, the public image of the company has been constructed around its founders, to the extent that Laurence Fink in particular has come to personify the company’s public identity and leadership. Although BlackRock has been publicly listed since 1999 it also has a complicated ownership structure (with shareholders divided into Investor A, B, C, Institutional and Class R share categories, with institutional investors holding a majority of the company’s stock). The two largest individual investors – Larry Fink and Susan Wagner, both original founders – hold 1.27% and 0.28% of the outstanding shares respectively, suggesting that while the popular image may be convenient for public relations and marketing purposes it is likely that BlackRock’s overall strategic management and control is subject to the approval and ongoing support of other individuals and corporate interest groups who are the real power(s) behind the public throne (discussed briefly in the following section).

State Street Corporation

State Street Corporation was founded in 1792 and its corporate headquarters is in Boston, Massachusetts. Like BlackRock, it is publicly-listed (on the New York Stock Exchange) and as of early 2024 had approximately $4 trillion of assets under management administered by approximately 46,000 employees. There has also been a high degree of continuity in terms of the board of directors and senior management: Joseph Hooley was Chairman and CEO from 1986 until 2017, while Ron O’Hanley was appointed President in 2017 and is currently the Chairman, President and CEO. O’Hanley joined State Street from Fidelity MR(!!), where he was the head of Asset Management and Corporate Services. He has also served on the Federal Reserve System’s Federal Advisory Committee, and as of June 2024 was a Class A Director of the regional Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. The configuration of the company’s ownership structure and the main institutional shareholders are discussed in the following section.

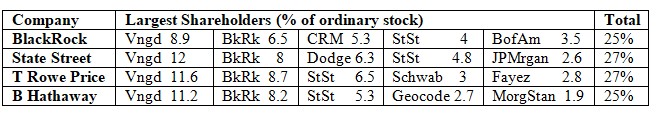

CLOSING THE LOOP? TIGHTENING THE NOOSE? OR FUSION AT THE CORE?

A crucial feature of recent developments that appears to have played a pivotal role in the construction of an elaborate system of centralized ownership and control by a small number of gigantic financial firms is the existence of a series of overlapping rings and networks of linkages and connections involving a multitude of bilateral and multilateral forms of cross-ownership. Moreover, in general terms the closer one gets to the centre of this interlocked cluster of financial ownership and power the more intertwined and confusing their ownership structures become. This appears to provide a closed loop or fusion of ownership, representation, participation, governance, control and accountability at the centre, emphasizing the fact that – despite the extremely complicated and diverse variety of corporate structures and linkages involved – these core financial entities collectively constitute the end of the line in terms of the ultimate corporate and financial chains of ownership, command and control (notwithstanding that it remains impossible for outsiders to identify an end point of supreme authority and decision-making power as such).

In terms of the specific types of corporate linkages and relations of cross-ownership that have formed at the core in the US, Vanguard is the largest institutional investor in all of the publicly-listed companies located around the centre (BlackRock, State Street, T Rowe Price and Berkshire Hathaway), with a stake of around 9-12% in each. However, as noted above the real ownership and control of Vanguard itself is just as difficult to determine given its sui generis corporate form and decision-making structures and procedures. Meanwhile, BlackRock owns 6.5% of its own stock through a controlled entity and also owns at least 8% of the stock in State Street, T Rowe Price and Berkshire Hathaway. State Street also has a significant stake in all of the other publicly-listed companies (BlackRock, T Rowe Price and Berkshire Hathaway), as well as in its own stock. A simplified estimate or quantification of the relations of cross-ownership among the largest firms at the centre of the financial core in the US is presented below (Table 6), based on the four largest institutional shareholders of the respective companies (as of June 2024).

TABLE 6

The identity of the ultimate decision-makers who control each firm, the group of people who really determine the respective companies’ overall investment strategies and objectives and make the most important operational management decisions, must therefore remain an open one. If this information exists in the public domain the present author has not been able to find it, beyond the public image of high profile individuals such as founders, significant individual shareholders or senior executives. While it is of course possible that a group of twenty or thirty directors and senior managers within each firm are the final authorities and power brokers, it is submitted that it would be naïve to simply take for granted that the formal institutional decision-making mechanisms and procedures of the companies are where the most important decisions are made – in forums such as the official meetings of the boards of directors or general meetings of the owners/ investors/ shareholders/ clients of specific investment funds and corporate entities within the umbrella group of each central holding company. Moreover, given the sheer scale of financial power and corporate control that the largest firms have managed to accumulate between themselves within a very short period of time, it would not be unreasonable to suppose that there are numerous other very wealthy and powerful individuals and interest groups embedded within the main power structures.

RELATED DEVELOPMENTS AND TRENDS AT THE INTERNATIONAL LEVEL

The following sections present a brief summary and overview of several key trends and developments related to a corresponding concentration of financial power and corporate ownership at the international level. These developments are considered from two separate angles: a brief survey of several national economies, while the second analytical perspective involves the underlying structures and characteristics, the major participants, and the governance or operational management of a selection of international financial systems and market sectors. Two aspects in particular will be covered: the formation of a similar central core of increasingly interlocked or fused cross-ownership networks and relationships which appear to be controlled by a tightly interconnected cluster of the largest firms at the centre; and, some of the ways in which the dominant firms based in the United States have projected their financial power and control over corporate governance and economic development into other countries and strategic market sectors.

More Fusion at the Core?

At the international level, it is immediately apparent that beyond the extraordinarily complex and diverse legal, financial and corporate forms and organizational structures involved, as well as the differences that exist among specific jurisdictions and markets, a similar arrangement or condition of extreme concentration of financial ownership and power has been achieved by a small number of tightly interconnected companies. This is particularly the case among the largest financial corporations of the United States, the United Kingdom and Europe (the latter dominated by companies incorporated in Germany, Switzerland and France).

A pioneering study of the ‘network of global corporate control’ in 2011 provides a useful starting point to analyse the main types of strategies and networking arrangements that have been developed by each of the companies at or near the centre of financial power and corporate ownership at the international level, the degree to which they are all interconnected among themselves, and the extended networks of corporations and industries that the firms at the centre have a significant interest in (which can also be described as their economic footprint). (Vitali et al., 2011) With respect to the underlying nature, tendencies and characteristics of the international network of corporate ownership and control as well as the findings and conclusions that could be drawn from the information reviewed, the authors surmise that:

“Certainly, it is intuitive that every large corporation has a pyramid of subsidiaries below and a number of shareholders above. However, economic theory does not offer models that predict how TNCs globally connect to each other. Three alternative hypotheses can be formulated. TNCs may remain isolated, cluster in separated coalitions, or form a giant connected component, possibly with a core-periphery structure…

(Within this broader conceptual and analytical context the study found that) the TNC network has a bow-tie structure… Its peculiarity is that the strongly connected component, or core, is very small compared to the other sections of the bow-tie… The core is also very densely connected, with members having, on average, ties to twenty other members… In other words, this is a tightly-knit group of corporations that cumulatively hold the majority share of each other… The top holders within the core can thus be thought of as an economic ‘super-entity’ in the global network of corporations. A relevant additional fact at this point is that three quarters of the core are financial intermediaries.” (Vitali et al., 2011, pp.4-5)

Of the corporations identified as constituting part of the most tightly interlocked nucleus (of which there are 147), a substantial majority are based (or have major listings and dealings) in the US (including AXA, Franklin Resources, T Rowe Price, Merrill Lynch, JP Morgan Chase, Prudential Financial, Morgan Stanley, Citigroup, Bank of America, State Street Corporation, Goldman Sachs, and Bear Stearns), with a much smaller number based in the United Kingdom (the most prominent of which was Barclays), Switzerland (UBS, Credit Suisse) and Germany (Deutsche Bank, Commerzbank). As noted in the following section, there is considerable overlap between these companies at the core of the international network of corporate control and the major players in and managers of the ‘offshore’ financial system.

Another more recent study of underlying or embedded corporate structures and networks within the system of financial ownership internationally confirmed the initial findings and conclusions of Vitali et al. and provides some further insights and perspectives on the phenomenon (Haberly & Wojcik, 2016). In terms of the key features and characteristics of ownership and control in the international financial system(s) that the analysis revealed:

“Empirically, we show that three quarters of the world’s 205 largest firms by sales are linked to a single global company network of concentrated (5%) ownership ties. This network has a hierarchically centralized organization, with a dominant ‘global network core’ of US fund managers ringed by a more geographically diverse ‘state capitalist periphery’…

The 20 most influential world investors by ‘economic footprint’ … are direct and ultimate 5% block holders in 56% and 61% of sample firms respectively. Fifteen of these 20, moreover, are direct 5% block holders in one another, with the global company network thus having an exceedingly compact interconnected nucleus… Seven of these fifteen mutually-invested network core members are based in the United States, with the two largest US passive managers, BlackRock and Vanguard, having vastly larger direct 5% control footprints than any other investors worldwide.” (Haberly & Wojcik, 2016, pp.14-15)

Hence, as in the United States, it is difficult if not impossible for outsiders to identify a final end point of supreme authority and strategic control given the high degree of interlinked ownership among the corporate entities at the top of the pyramid (or the centre of the core) within which most corporations own a substantial number of shares in one or more of the others, reinforced by multiple layers of cross-ownership (mutual ownership of shares between two corporations) and self-ownership (where a separate legal entity or investment fund owned by one of the corporations holds shares in the parent company). Almost fifty years earlier, Kwame Nkrumah (the first president of Ghana after independence) made some similar and remarkably perceptive observations concerning the underlying power structures and emerging characteristics of the international financial system and corporate ownership and control:

“American finance capital, of course, had a field day in Germany during the post-war occupation. German industry and finance, already linked to American industry and finance by cartel and trust arrangements, became even more heavily penetrated by the powerful United States monopoly groups.

The giant German banks … are all strung to American capital and in many ways subordinate to it. Italian banks and industry are in much the same position… Examples can be stretched across the world, to Japan, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand… The rule of the financial oligarchy is maintained through the principal device of the ‘holding company’, often established with a purely nominal capital but controlling direct and indirect subsidiaries and affiliates utilising vastly superior finances…

[The emergence of financial consortiums controlling vast corporate empires] are in fact the merest directional indications of today’s trend of ever-tightening links between a short list of incredibly powerful groups that dominate our lives on a global scale… [The financial power wielded by these groups has steadily grown over time, spearheaded by] the constant penetration by a few banking and financial institutions into large industrial and commercial undertakings, creating a chain of links that bring them into a connective relationship making for domination in both national and international economy.

The influence exercised by this domination is carried into politics and international affairs, so that the interests of the overriding monopoly groups govern national policies. Their representatives are placed in key positions in government, army, navy and air force, in the diplomatic service, in policy-making bodies and in international organisations and institutions through which the chosen policies are filtered on to the world scene.” (Nkrumah, 1966, pp.44-80)

The financial and industrial barons of the early 1900s in the US typically exercised their financial power directly, if not flamboyantly on some occasions. In more recent times the concentration, consolidation and deployment or utilization of this immense inherent or structural financial power is not usually as direct and apparent to the public. Indeed, in most cases it is not even possible to state from the information available in the public domain who really owns and controls the respective private financial institutions, with most attention focused on the statements of a few high profile founders and senior executives who often only account for a small percentage of the overall ownership or voting rights. Meanwhile, behind the stage curtains the cluster of tightly interconnected corporate entities at the centre of the core layers of financial ownership and corporate control have fused to such an extent that it appears to have become a nebulous blob whose external contours and boundaries are constantly expanding, permeating and diffusing through the entire system to such an extent that it is impossible to say where the central corporate nucleus ends and how much – if anything – really remains of ‘the free market’ or ‘the financial system’ as autonomous concepts and constructs.

The Projection of Centralized Financial Power

A second aspect that is particularly noteworthy at the international level is the ways in which some of the largest companies have leveraged their commanding position in the United States and Europe to project their immense financial power into other countries, strategic economic sectors and international financial markets. While the detailed study by Fichtner et al. found that Vanguard and BlackRock have concentrated the majority of their ownership stakes in the United States, they have nonetheless managed to project their financial power internationally using several key strategies and methods. Perhaps the most significant of these is the extent to which they have acquired large stakes in other major financial companies and institutional investors in strategic sectors and markets throughout the world, particularly in Europe, companies which themselves often occupy a basically similar privileged if not quite so all-powerful and pervasive position in the financial system of countries in Europe and elsewhere:

“At the international level, the largest US passive manager, BlackRock, is by far the most influential actor in global network integration… BlackRock holds a direct 5% stake in nearly a third of sales-weighted sample firms worldwide, a proportion which rises to 45% for its ultimate 5% pyramid. Outside of the US, Blackrock’s footprint is most concentrated in the UK, where 92% of sample firms lie within its 5% pyramid… (Also notable in this respect is) the concentration of BlackRock’s non-Anglo-American holdings in financial multinationals with large free floats and US listings or quotations (e.g. Deutsche Bank, AXA, UBS, BBVA, ING, Zurich Financial, Mitsubishi UFJ).” (Haberly & Wojcik, 2016, p.18)

A related manifestation of the extended financial power that the largest US companies wield over the economies of other countries and international markets is derived from their substantial ownership position in the other major financial companies based in the US (such as JP Morgan and Citigroup), which as noted above also have a prominent presence in key economic sectors in numerous countries. For instance, a small number of firms at the core have gained effective control over most of the Australian economy through an intermediate layer of financial ‘proxies’, through which they also control some of the most important mining projects in Colombia (and of course in a long list of other countries in Latin America, North America, Africa and elsewhere, whether through the same corporate proxies or others).

Meanwhile, in Canada the ownership of the largest publicly-listed companies also demonstrates a significant degree of concentration, but not as much as in Australia (and with different firms occupying the most dominant ownership positions). Although the configuration of a relatively closed loop of financial ownership and control formed at the centre by a small group of interconnected companies is also clearly apparent, the situation in Canada is nonetheless quite distinct from Australia in several key respects. In the latter country the degree of closure is extreme, consisting of just three or four members (all foreign financial companies) who between them have a majority or near majority stake in almost all of the publicly-listed companies surveyed.

In Canada, the closed loop of ownership at the centre is not as tight, and it is composed mostly if not entirely of a cluster of Canadian banks (Royal Bank of Canada, Bank of Montreal, Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, Toronto Dominion Bank, the Bank of Nova Scotia, and National Bank of Canada) which generally hold a combined direct stake of at least 20-30% in publicly-listed companies (as well as each other). Of these, the Royal Bank of Canada and Bank of Montreal are undoubtedly the dominant members of the ‘stock exchange cartel’, usually constituting the two largest shareholders with stakes of around 8-9% and 5-6% respectively. Vanguard is also among the ten largest institutional investors of many companies (usually holding around 4%), but BlackRock does not have many significant direct shareholdings in the country. Other senior members of the secondary level of the nucleus of the Canadian financial system would likely include Mackenzie Financial Corporation and 1832 Asset Management.

Related Developments in the ‘Offshore’ Financial Markets

As a final illustrative example of international trends, an analysis by James Henry provides another distinct perspective on the evolution of an extraordinary degree of market concentration and centralization of ownership and control within key sectors of the international financial system (Henry, 2012). The study reviews the Private Banking Assets Under Management and Total Client Assets of the fifty largest Global Private Banks between 2005 and 2010 (with a specific focus on ‘cross-border assets under management’ – in effect, a proxy indicator for a major sector of the ‘offshore’ financial system). The findings of the analysis suggest that in much of Europe (particularly Germany, Switzerland, France and the United Kingdom) a very limited number of corporations have also established a high degree of market concentration in this component of the offshore system. Specifically, the twelve largest financial institutions identified were: UBS and Credit Suisse (both with over $900 billion in total international client assets); followed by HSBC and Deutsche Bank (more than $600 billion); PNB Paribas, JP Morgan Chase, Morgan Stanley and Wells Fargo (more than $500 billion); Goldman Sachs, Pictet, Bank Leumi and Barclays (over $400 billion). Between them, the top ten firms controlled over 50% over the total market.

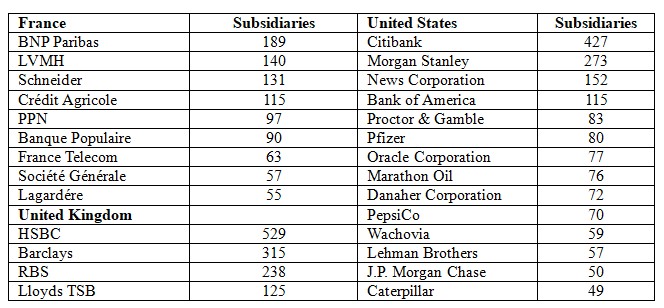

With respect to tax havens and secrecy jurisdictions generally, a study conducted by the Government Accountability Office (GAO, 2008) to examine the subsidiaries of a selection of US companies (focusing on major federal government contractors) found that, of the companies reviewed, Citigroup had the most subsidiaries in countries listed as tax havens or ‘financial privacy jurisdictions’. According to its financial statements, 427 of Citigroup’s subsidiaries listed with the Securities and Exchange Commission were located in tax havens. However, the study also notes that the list may not be complete as the Securities and Exchange Commission only requires listing of ‘significant subsidiaries’.

Another study commissioned by the British Trades Unions Congress in 2009 found that the five largest banks in Britain (Lloyds, TSB, RBS, HSBC and Barclays) have over 1200 subsidiaries in tax havens, noting that: “As with the US and British studies: while plenty of companies have numerous tax haven subsidiaries, it is the banks and financial companies that tend to stand out… All of them (the five largest banks), it turns out, have a substantial presence in tax havens.” (TJN, 2009a) The following table lists the number of subsidiaries owned by major companies based in the US, the UK and France that are registered in jurisdictions classified as tax havens. The data was compiled from reports completed by the Tax Justice Network and the Government Accountability Office (TJN, 2009a; TJN, 2009b; GAO, 2008).

TABLE 7

Even these figures can only be considered a very preliminary and incomplete estimation of the extent of each company’s involvement in ‘offshore’ markets and tax havens. As the GAO study notes, it is usually impossible to know just how deep and how far these extended networks go because the companies can easily adjust their corporate structures and investment vehicles to minimize reporting requirements. For example, Martens (2014) notes of Citicorp: “In its filing for December 31, 2008, Citigroup told the SEC it had 2,245 subsidiaries. By December 31, 2009, just one year later, it was claiming just 187 principal subsidiaries. At the end of 2013, it reported that number at 184.”

Over the last thirty or forty years it has become standard practice for the largest conglomerates to intensify their reliance on ‘creative accounting’, parallel financial transactions and corporate restructures to channel their commercial and financial activities and dealings through tax havens and secrecy jurisdictions. A detailed analysis by Raymond Baker (2005) estimated that around half of all international commercial transactions pass through tax havens. In terms of the main protagonists and players who are most actively involved in the organization and operational management of particular offshore markets and accounts, Henry (2012, p.32) comments that:

“While there are now over 500 private banks, hedge funds, law firms, accounting firms, and insurance companies that specialize in offshore, the industry is actually very concentrated. Most of its employees work directly or indirectly for the world’s top 50 private banks, especially the top 21 that now each have private cross-border ‘assets under management’ of at least $100 billion each.”

Beyond the inherent complexity of the individual corporate structures and financial transactions involved, typically passing through multiple offshore jurisdictions and a series of corporate entities which provide an impenetrable shield of secrecy and confidentiality, is the technical and logistical difficulties faced by individual countries and regulatory agencies responsible for monitoring and regulating these activities. In this respect, a review conducted by the National Audit Office of the United Kingdom states:

“Complexity is a growing challenge. For example, the Cayman Islands are home to 80 per cent of the world’s hedge funds… The global effects have been exacerbated by lack of transparency over the ownership and scale of risks. Hedge funds … have structures which split regulatory responsibility internationally. Typically, key intermediaries will be in onshore financial centres, while the funds’ registration and administration will be offshore.

As hedge funds are primarily intended for institutional and expert investors, they have traditionally been subject to lighter regulations. However, there are growing calls for more regulatory oversight in areas such as corporate governance, valuation of assets, disclosure and adherence to the fund prospectus. Such regulations would, to be completely effective, have to be imposed on the fund itself by offshore regulators. Even for the larger regulators worldwide it is a challenge to find enough skilled resources effectively to enforce such regulation.” (NAO, 2007, p.20)

Yet another factor that constitutes a potential risk to the accuracy and reliability of corporate financial statements, as well as market efficiency, systemic risk and stability in the financial system generally, is that the ‘independent’ auditing of the financial management, statements and accounts of almost all of the largest corporations is conducted by ‘the Big 4’ accountancy firms – PricewaterhouseCoopers, Deloitte, Ernst & Young, and KPMG (see for example Harari et al., 2012; Tax Research UK, 2010). The multitude of inherent conflicts of interest, ‘arm’s length’ dealings between related parties, and other similar tendencies which have become common practice in the modern era constitute major challenges and potentially very severe risks to the integrity and genuine independence of the auditing and accountability of the major financial firms, and the integrity and stability of the financial system as a whole.

Such features and tendencies are exemplified by the provisions applying to the Federal Reserve System (FRS). The Government Accountability Office (the main auditing agency of the Congress) was authorized to conduct its first ever audit of the FRS in 2011 as the controversy concerning the ‘bailout’ of the financial sector in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis became impossible for the politicians and regulators to continue to shrug off. The audit was however extremely limited in its scope, only covering events and transactions directly pertaining to the main emergency programs and loans involved.

The investigation determined that there was a general lack of transparency in the administration of activities and dealings related to the bailout program, and that many of the existing guidelines and requirements were not applicable or relevant to the implementation of the emergency bailout program (for example, many contracts for the acquisition of ‘vendor services’ were awarded in a non-competitive manner). The report also found that senior executives and managers of some of the firms that received very substantial bailout packages had previously served as directors of the regional Federal Reserve Banks or been employed by the FRS at some point in their career, and that the FRS’s conflict of interest provisions were routinely waived or ignored during the bailout program. Meanwhile, the investigation also found that approximately 40% of the $16 trillion allocated to the emergency loans and assistance program was granted to three of the most influential member banks of the FRS: Citigroup (around $2.5 trillion, give or take a few billion), Morgan Stanley ($2 trillion) and Merrill Lynch ($1.9 trillion).

In its publications and bulletins, the FRS typically emphasizes the multiple layers of accountability that it is subject to. These include its own internal financial management and auditing procedures, certification of its financial statements by the auditing firm Deloitte, and supervision by the Congress. There is also a federal officer whose position was created for the specific purpose of reviewing certain activities (the Federal Reserve Board Office of the Inspector General), however the office’s functions are largely limited to ‘auditing’ the policies of the Board of Governors. In this respect, the GAO investigation (titled “FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM: Opportunities Exist to Strengthen Policies and Processes for Managing Emergency Assistance”) commented that:

“The Reserve Banks’ and LLCs’ (Limited Liability Corporations) financial statements, which include the emergency programs’ accounts and activities, and their related financial reporting internal controls, are audited annually by an independent auditing firm. These independent financial statement audits, as well as other audits and reviews conducted by the Federal Reserve Board, its Inspector General, and the Reserve Banks’ internal audit function, did not report any significant accounting or financial reporting internal control issues concerning the emergency programs.” (GAO, 2011, p.2)

If systemic integrity, transparency and accountability are to be recovered, one of the fundamental tasks is the development and implementation of genuinely independent and ‘arm’s length’ auditing procedures and requirements (see for example Strange, 1996; TJN, 2017; TJN, 2018; Fattorelli, 2013; Transparency International, 2012). More generally, Korten (1995, p.212) states of the underlying support structures and the operational management of the ‘free’ market and the financial system:

“We hear repeatedly from defenders of corporate libertarianism that the greening of management within a globalized free market will provide the answer to the world’s social and environmental problems. With financial markets demanding short-term gains and corporate raiders standing by to trash any company that isn’t externalizing every possible cost, efforts to fix the problem by raising the social consciousness of managers misdefines the problem. There are plenty of socially conscious managers. The problem is a predatory system that makes it difficult for them to survive.”

CONCLUSION

By any measure, the breadth and depth of market concentration in the financial sector and of the centralization of economic power and planning is extraordinary, both within many national economies as well as in most international financial systems and market sectors. The owners, senior executives and operatives of Vanguard and BlackRock in particular appear to have achieved a level of centralized decision-making and control over financial management and economic planning and development that far exceeds anything that was ever achieved by the central Politburo of the Communist Party in the Soviet Union at the peak of its power. While it is submitted that the tightly interlocked and secretive system of ownership and control over the financial system and corporate governance should be subjected to a thorough investigation and ultimately partially if not completely dismantled or disaggregated in some way so that economic diversification and autonomous markets can be restored or reconstructed, it does not make sense to speak of actions such as ‘nationalization’ or ‘expropriation’ as such because, as noted above, the overwhelming majority of the funds that the exclusive club of interconnected finance companies and asset managers are using is not their own money in the first place. In any case, these are matters that require much more analysis and public debate, in the first place to understand what has happened and how the current configuration of ownership and control is structured and managed, and secondly in order to consider whether and if so how the existing financial system, corporate governance arrangements, and economic planning and development roles and functions can be modified or reformed.

REFERENCES

- Baker, R. (2005). Capitalism’s Achilles Heel: Dirty Money and How to Renew the Free Market System. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

- Benjamin, M., & Davies, N. (2018). War Profiteers: The U.S. War Machine and the Arming of Repressive Regimes. Washington DC: Code Pink.

- Bloomberg. (2018). Company Overview of the Vanguard Group, Inc. Bloomberg.

- Board of Governors. (2005). The Federal Reserve System: Purposes & Functions (Ninth ed.). Washington DC: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

- Chomsky, A., Leech, G., & Striffler, S. (2007). The People Behind Colombian Coal: Mining, Multinationals and Human Rights. Bogota: Casa Editorial Pisando Callos.

- Christian Aid. (2013). Invested Interests: The UK’s overseas territories hidden role in developing countries. London: Christian Aid.

- Edgar, D. (2019). Mining and Indigenous Peoples in Colombia – Part III. [E-reader Version]. Daniel Edgar: Independent Academia.

- Fattorelli, M. (2013). Citizen Public Debt Audit: Experiences and methods. Liege: CADTM.

- FRS. (2013a). Current FAQs: Who owns the Federal Reserve? Federal Reserve Bulletin.

- FRS. (2013b). Current FAQs: Who are the members of the Federal Reserve Board, and how are they selected? Federal Reserve Bulletin.

- Fichtner, J., Heemskerk, E., & Garcia-Bernardo, J. (2017). Hidden power of the Big Three? Passive index funds, re-concentration of corporate ownership, and new financial risk, Business and Politics, (April 2017), pp.1-28.

- GAO. (2008). International Taxation: Large U.S. corporations and federal contractors with subsidiaries in jurisdictions listed as tax havens or financial privacy jurisdictions. Washington DC: Government Accountability Office.

- GAO. (2011). Federal Reserve System: Opportunities exist to strengthen policies and processes for managing emergency assistance. Washington DC: Government Accountability Office.

- Haberly, D., & Wójcik, D. (2015) Earth Incorporated: Centralization and Variegation in the Global Company Network. [E-reader Version]. Economic Geography, 93(3), pp.241-266.

- Harari, M., Meinzer, M., & Murphy, R. (2012). Key Data Report: Financial Secrecy and the Big 4 Firms of Accountants. London: Tax Justice Network.

- Harker, J., Kalmonovitz, S., Killick, N., & Serrano, E. (2008). Cerrejon Coal and Social Responsibility: An Independent Review of Impacts and Intent. Bogota: Cerrejon Coal.

- Henry, J. (2012). Revised estimates of Private Banking Assets Under Management and Total Client Assets – Top 50 Global Private Banks 2005-2010. London: Tax Justice Network.

- Korten, D. (1995). When Corporations Rule the World. London: Earthscan.

- LMN et al. (2009). BHP Billiton – Undermining the future: Alternative Annual Report 2009. London Mining Network, Friends of the Earth, Colombia Solidarity Campaign.

- Martens, P. (2014). 2,061 of Citigroup´s Subsidiaries go Missing. Wall Street on Parade, 11 August 2014.

- Murphy, R. (2008). Tax Havens: Creating Turmoil. London: Tax Justice Network.

- NAO. (2007). Managing Risk in the Overseas Territories. London: National Audit Office.

- Nkrumah, K. (1966). Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism. London: Panaf Publications.

- OECD. (2008). OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. Paris: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- SCG. (2010). External technical review report regarding progress in the implementation of the recommendations of the Third Party Review. Lima: Social Capital Group.

- Strange, S. (1996). The Retreat of the State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tax Research UK. (2010). Where 4 Art Thou? A geographic study of the Big 4 firms of accountants”, Cambridgeshire: Tax Research UK.

- TJN. (2009a). Major Corporations and Tax Havens. London: Tax Justice Network.

- TJN. (2009b). New Study: Tax haven subsidiaries of CAC-40 companies. London: Tax Justice Network.

- TJN. (2017). Lobbyism in International Tax Policy: The long and arduous path of Country-by-Country reporting. London: Tax Justice Network.

- TJN. (2018). Accounting (f)or Tax: The Global Battle for Corporate Transparency. London: Tax Justice Network.