This analysis originally appeared at southfront.org on August 28, 2017

The Syrian Arab Navy was established in 1950 following the procurement of a number of naval vessels from France and the initial training of Syrian military officers at the French naval academy, forming the core of competent naval officers from which to expand the nation’s navy. The main Syrian naval bases are located at the seaports of Latakia and Tartus, as well as at Baniyas and the Al-Mina al-Baida Marine Base. Latakia is Syria’s largest port and is also equipped with a naval repair dockyard. A squadron of “fast attack craft” (FAC) armed with anti-ship missiles, guns, and/or torpedoes are based at Latakia.

Tartus is also an important base for the Syrian Navy in the Mediterranean Sea. It hosts a Soviet-era naval supply and maintenance base, first established under a 1971 agreement between the two countries. Prior to its modernization, the Russian naval facility consisted of three floating dry docks, dry and liquid storage, military barracks and other facilities. Since 2015, Russia has been renovating the Tartus naval base, dredging the port and deepening the main channel to allow access for its larger naval vessels. Russia began a five year plan to expand and modernize the port in the spring of 2017 and is intent on developing the current facility into a large naval base that can support and service 11 large warships. A fuel pipeline is being constructed, as well as the reinforcement of quay walls and the breakwater.

The Syrian Navy indirectly fought in the 1956 war alongside Egypt. It also participated in the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, but has only had a very limited operational impact on the current Syrian war. Currently, the Syrian Navy is led by Admiral Mohammed Al-Ahmad and has approximately 4,000 officers and seamen, along with 2,500 in reserve. Russia, Iran, and China are the main foreign sources of vessels, equipment and weaponry to the Syrian Navy. The service is by far the smallest of the military branches, with an annual budget of only 50 – 150 million dollars prior to 2011.

Vessels in Service

Although the Syrian Navy and the Syrian Coast Guard possess 45 naval vessels, most of these are out of service for financial or technical reasons. The realities of the current conflict, with most fighting taking place in areas removed from Syria’s coast, and in light of the financial strains exerted on the nation as a result of six years of continuous war, the Navy has fallen into a state of disrepair and obsolescence. It does not stand as a viable deterrent to the coastal interdiction of either Israel or Turkey, the role of coastal defense largely determined by the Russian military presence in the region.

Al-Assad Training Vessel: Built in the Poland in 1988 as a training vessel for cadets in the Syrian Maritime Academy; however, it can be used as a landing or troop transport vessel. In 2010, it was used during the evacuation of Syrian nationals from Libya. The vessel lacks any modern offensive or defensive weapons systems.

Two Petya III light frigates (project 159). Petya III is an export version of the Petya I and Petya II light frigates which were built by the Soviet Union in the 1960-1970s. Two ships are still technically in service in the Syrian Navy as anti-submarine (ASW) frigates. Each is armed with anti-submarine mortars, two twin 76 mm guns, 4 RBU-6000 anti-submarine rocket launchers and one triple 533 mm anti-submarine torpedo tube. The vessels were re-fitted by Russia in 2000; however, the frigates rarely put to sea, due to the relative neglect of the ships and the poor state of the Syrian Navy.

12 OSA II / OSA I missile boats (project 205). Sixteen OSA class missile boats were built for the Syrian Navy in the Soviet Union in late 1960s through the 1980s. They are armed with 2 AK-230 twin 30 mm CIWS and four P-15 Termit anti-ship missiles with an effective range of 80km. The boat’s shallow 9.5 foot draft and a high speed of 40 knots gives it great flexibility in operating from protected coves. It is a coastal patrol vessel, with an endurance of five days, and an operating range of 800 nautical miles at a cruising speed of 30 knots. Currently, many of the OSA Class boats are out of service due to disrepair and the financial prioritization of the Army and Air Force.

Fig. 5 Syrian Navy Tir II missile boat launching a Chinese made C-802 anti-ship missile (or Iranian produced analog called the Noor) anti-ship missile during drills.

6 Iranian manufactured Tir II missile patrol boats. These small and fast attack craft were transferred to the Syrian Navy in late 2006 or early 2007. Each boat is armed with two Chinese made C-802 anti-ship missiles or Noor (Iranian produced analog) ASMs with an effective range of 120 km. These small fast attack missile boast are the newest vessels in the Syrian Navy. These vessels are of extremely limited endurance and range, yet offer a very powerful anti-ship deterrence on a very small and economical platform. They are extremely cost effective and easy to maintain.

3 Polish Polnocny-B (Project 771) landing ships. The Polnocny class ships were a joint Polish-Soviet design, dating from the late 1960s. They are classified as medium landing ships, or Landing Craft Tank (LST). The B variants have a displacement of 834 tons, and an LOA of 73 meters. They are all out of service for financial and technical reasons. It is worth noting that ships of this class were removed from service and scrapped in the early 1990s.

One Sonya mine hunter coastal (project 1265). This wooden hulled minesweeper was built for the Syrian Navy in the Soviet Union in 1973. It is likely armed with two quadruple MANPAD 9K32 Strela (SA-14), two AK-230 twin 30 mm CIWS, and one 2M twin 25 mm CIWS. It is also fitted with deep contact sweep GKT-2, loop electromagnetic sweep PEMT-4, solenoid electromagnetic sweep ST-2 and mine hunter KIU-1 underwater mine detection systems.

One Natya minesweeper ocean (project 266M) was built for Syrian Navy in the Soviet Union in 1981. The vessel is armed with two quadruple MANPAD 9K32 Strela (SA-14), two AK-230 twin 30 mm CIWS and two 2M twin 25 mm CIWS, two 12.7 mm DSHK, and two quintuple RBU-1200 anti-submarine mortars. A mine hunter KIU-1 and fast contact sweep underwater mine detection systems are fitted.

Five Yevgenia minesweepers inshore (project 1258). These vessels were built in the Soviet Union for the Syrian Navy in the 1970s and 1980s. They are armed with two quadruple MANPAD 9K32 Strela (SA-14), one twin 14.5 mm machine gun, one 55 mm grenade launcher system and mine detection systems of varying types. Most of these vessels are not in service for technical reasons.

Two or Three Romeo Class diesel electric coastal submarines. Syria had operated three Romeo class submarines in the past. They were built in the Soviet Union in 1960 and transferred in 1985-86. It appeared that the Syrian Navy hoped to establish a small submarine force, and used the vessels as training platforms for submariners and in wargames with its fleet of ASW ships to help train crews to detect and counter submarines; however, Syria decommissioned these submarines after one of them was disbanded and dismantled. Maintaining and operating even a small, viable submarine force is extremely demanding, and it is most probable that it was not seen as a priority after the internal conflict in Syria gained momentum.

The Syrian Coast Guard

Vessels in Service

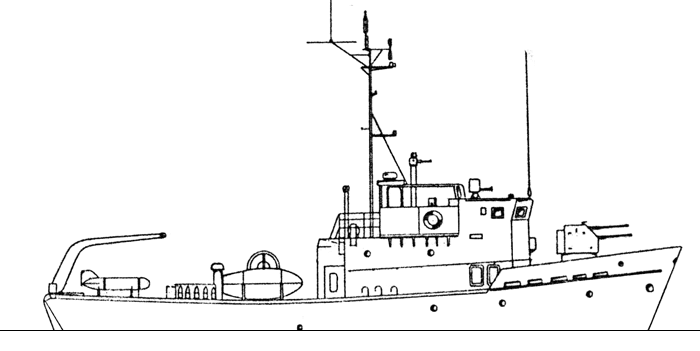

8 Soviet-made Zhuk naval patrol boats (project 1400 ME). They were built for the Syrian Navy in the Soviet Union between 1980 and 1985. They are armed with twin 12.7 mm machine guns in fore and aft mounted turrets.

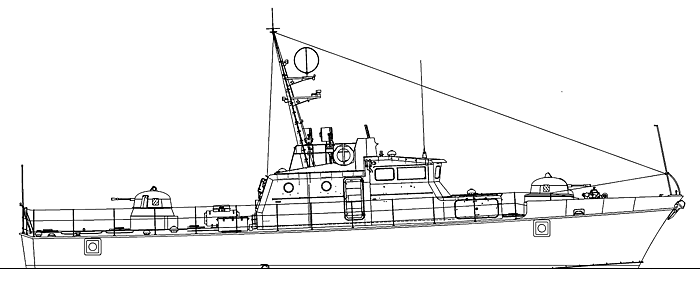

6 Iranian-made MIG-S-1800 marine patrol boats. These small vessels are typically armed with a 20mm gun and 12.7mm, as well as crew carried small arms.

Naval Aviation and Anti-Submarine Warfare Aviation

The 618th Maritime Warfare Squadron comes under the establishment of the Syrian Navy. The squadron is equipped with a number of Soviet made rotary wing ASW aircraft. Helicopter ASW platforms lack the range of fixed wing aircraft; however they can provide some coastal ASW capability and have the benefit of being able to loiter for extended periods at short range from their coastal bases. They can also provide search and rescue duties as a back-up function.

11 Mi-14PL anti-submarine amphibious helicopters. Intended to be armed with twelve 50 kg & eight 250kg bombs and one multi purpose self-guided torpedo. Most of these large helicopters are used in the current Syrian war to assist with transport and bombing tasks, using homemade bombs. With little threat of a naval attack at present, especially from hostile submarines, the helicopters are not utilized in their intended ASW role.

4 Ka-25 anti-submarine helicopters. Units are typically armed with eight 50 kg/four 250kg bombs and two torpedoes.

4 Ka-28PL anti-submarine helicopters. An export version of the Ka-27PL (first produced in 1981), it is typically armed with 250kg bombs and torpedoes. They are also used in the current Syrian war to carry out transport missions and for ground-based bombing missions, using OFAB (HE) bombs.

Coastal Defense

While most of the vessels operated by the Syrian Navy are either obsolete, in an unseaworthy state, or of very small displacement, the Syrian coastal defense forces are considered to be quite capable. Syria has in operation a number of older Soviet designed surface-to-surface missile systems meant to engage surface targets at sea. A number of newer coastal defense missile systems and targeting radars have been provided in recent years by Russia, including the Bastion P armed with the P-800 Yakhont (Onyx) anti-ship cruise missile (ASCM). Systems currently in service include:

Soviet naval defense system 4K51 Rubezh (Nato designation SS-C-3 Styx). The system is relatively simple, and all components (missiles, control module and radars) are mounted on one vehicle, an 8×8 heavy off-road MAZ-543 truck. The 4K51 is thus self-contained and autonomous. This makes the system quite flexible in deployment, easy to position and reposition, and concurrently hard to target. Each truck is armed with two P-20 or P-21 Termit anti-ship missiles in large semi-cylindrical launch tubes. These missiles are guided either by active radar or infrared guidance depending on the variant employed and have an effective range of 80 km. The vehicle makes use of either an MR-331 Rangout or 3Ts-25 Garpun acquisition/targeting radar; however, it has the ability to be guided by more advanced radar based on warships or aircraft.

Soviet coastal defense system 4K44B Redut. This system comprises one radar and command vehicle, and up to three missile launch vehicles. The launch vehicles each carry only one P-35 Shaddock long-range anti-ship missile, due to the extremely large size of the projectile. These missiles have an effective range of 300 km. Syria deployed this system after the American cruise missile strike on Shaareat airport on 7 April 2017.

Coastal defense batteries armed with the Chinese C-802 missiles or the Iranian version (Noor). These missiles have a range of between 30 and 170 km based on the variant, and are the most modern short range anti-ship missile in Syria’s arsenal. It is believed that missile of this type was used by Hezbollah to damage the Israeli ship INS Hanit, type Sa’ar 5 Class light frigate, on 14 July 2006 during Israeli- Hezbollah conflict of 2006. The missile hit the vessel from astern, but lucky for the crew, the missile exploded upon striking a safety railing and then an aft cargo crane, not upon impact with the hull or superstructure. A direct hit would have proven devastating.

Russian 3K55 Bastion. These modern and capable coastal defense missile systems are armed with the P-800 Yakhont/Oniks (NATO designator Strobile) long-range anti-ship missile. These supersonic missiles have a 300 km range, a top speed of over Mach 2.5 and pinpoint accuracy against land and sea based targets. Two squadrons (8 launch vehicles, command vehicles, support vehicles and loaders) were transferred by Russia to Syria in 2011. The Israeli Air Force attempted to launch a strike on the depot that they believed was housing these missiles in Latakia in July of 2013. Satellite imagery studied after the strike revealed that the depot did not explode, and it was surmised that the missiles were moved before the airstrike. In late 2016, Russia used Oniks missiles to strike al-Nusra HQs in Idlib during its Dawn of Victory operation.

The Syrian coastal defense also utilizes conventional coastal artillery batteries armed with towed artillery of high caliber, as well as rocket artillery. Although not guided weapons, such systems can be used as area effect weapons when a barrage of fire from multiple guns or launchers bracket a small area. Range and accuracy are limited.

130 mm towed field gun M-46. This cannon has a range of 27-35 km., and can fire a range of ammunition including armor piercing high explosive (APHE).

BM-21PD Damba rocket artillery. A 122mm. Grad rocket launcher on a truck chassis, the Damba is armed with forty PRS-60 missiles for use against underwater targets with a range of nearly 5 km. The rockets act in a similar function as depth charges, and can strike underwater targets within a range of depth between 3 to 200 meters. The Damba was designed as a defense against coastal submarines and divers engaged in infiltration and sabotage of port facilities, docked vessels and naval bases.

The Syrian Navy Forces also operate a variety of surveillance and detection systems. These powerful radars allow the Navy to monitor surface and air traffic well out to sea, and theoretically give advance warning of any attacks coming from that quarter. The most notable of these systems are:

Russian made coastal radar Monolit-B. It has a passive detection range of 250 km, and an active detection range of 450 km. It can detect up to 50 surface targets, and continuous track 10 of them for the purpose of targeting in conjunction with other weapons platforms.

Soviet-made coastal radar Mys-M1E. It has a detection range of 256 km, with the capability of tracking targets and has viable IFF (Identify Friend or Foe) capability.

Soviet/Ukrainian electronic warfare/communications surveillance system Kolchuga (Chainmail). Kolchuga is used in electronic and signal intelligence and can detect sea and air targets with negative patterns of up to 800 km. It does not operate like a conventional radar, and is only effective for detecting targets in line of sight of the system when deployed. Kolchuga does not operate like a traditional radar. The system detects radio transmitters mounted on targets and triangulates target location through the use of at least three powerful receivers. It is argued that Kolchuga may be able to detect radiation or electromagnetic interference created by aircraft engines and their exhaust.

Chinese made low-altitude radar Type 120 (LLQ120). The Type 120 is a modern, low altitude acquisition radar, used to detect low altitude aerial targets above sea level. The Type 120 likely operates in the L-band, and offers good target acquisition and tracking of terrain-following, low flying aircraft and cruise missiles.

Syrian Arab Navy in Action

The Syrian Navy has had little opportunity to play a decisive role in the current Syrian conflict. The obvious technical obsolescence of the Syrian fleet gives it little hope for any outstanding military successes; however, the Syrian Navy was able to contribute to the current military conflict in Syria by targeting the enemy and providing assistance to ground forces. As all of coastal Syria has been secured by the Syrian Arab Army and its allies, the Navy has little opportunity of providing any assistance to ground forces, other than the use of naval helicopters in transport missions, naval units must stay vigilant and increase operational readiness to deter any Israel military action along the southern coast.

April 10, 2011

First security operation in Baniyas – The Syrian Navy participated in the encirclement of the Baniyas city after the militants targeted a bus carrying Syrian Arab Army soldiers.

August 14, 2011

OSA II boats targeted militant sites in the Al Raml Shimaly district in Latakia using 30 mm guns.

May 2, 2013

Second security operation in Baniyas – Syrian naval vessels and the Coast Guard participated in an effort to interdict seaborne illegal weapons trafficking from the Lebanese city of Tripoli. Illicit arms were being trafficked from Tripoli to Baniyas via small boats, mostly under the cover of darkness.

The future of Syrian Navy

Between 2006 and 2009, there were many unconfirmed reports of Syria’s intention to purchase two modern Amur -1650 submarines (project 677 E) and two Steregushchiy (Vigilant) class corvettes (project 20380). The Steregushchiv Class corvettes are the latest corvette design in service in the Russian Navy and are quite large in displacement (2,200 tons), being designated as frigates by NATO. They are extremely capable and flexible warships and are good coastal defensive platforms, with a draught of only 3.7 meters (12 feet).

The procurement of two Amur Class submarines is perhaps wishful thinking. Syria’s submarine force is not technically capable of operating and maintaining new submarines at this juncture, and limited financial resources, if allocated to the Navy, should be spent on maintaining fast patrol boats already on inventory and in acquiring more small displacement warships that can secure Syria’s 193km. (120 mi.) coastline. Despite Russian approval of the deal, Syria was unable to finance the purchase. In light of realities on the ground, it was decided that funding more important sectors of the Syrian army and upgrading the nation’s air defense systems were of greater priority.

Moscow and Damascus previously signed an agreement to expand and modernize Russia’s naval facility in the Syrian port of Tartus. On January 20, 2017, it was revealed that under one of the terms of this treaty, Russia agrees to assist the Syrian army in rebuilding their naval forces. However, at this time, it is difficult to say what type of assistance will be provided.

It would be preferable for the Syrian Navy to modernize its coastal defense capabilities. Although Syrian naval vessels are quite old, a viable and robust Syrian Navy and coastal defense are essential to guarantee security. Since the 1980s, Syria did not have the financial capacity to build or buy modern naval vessels of significant size from other countries. The Syrian military decided that it was best to invest the available funds into modern coastal defense systems, seeing these systems as more cost effective. They also believed that these highly mobile systems offered greater mobility and thus, survivability in a conflict with either Turkey or Israel. This decision can be considered as quite logical; however, greater effort must be undertaken once the tempo of ground combat diminishes, to rebuild both the Syrian Navy and the Syrian Arab Airforce. Only then will Syria be able to step out of the shadow of its ally Russia to provide for the security of the Syrian people.