“Our defeat was always implicit in foreign victory: our wealth has always produced poverty for us in order to feed the prosperity of others – the Empires and their native administrators. In the colonial and neo-colonial alchemy, our gold was transformed into toxic waste, and our food was converted into poison.”

Eduardo Galeano, “The open veins of Latin America”

Written exclusively for South Front by Daniel Edgar

Part I focused primarily on domestic factors and dynamics underlying and shaping the tumultuous and unpredictable course of recent political developments in Colombia from the perspective of distinct political and economic actors, interest groups and social sectors. Part II extends the analysis to examine some of the most influential international and geopolitical dimensions and factors from the Cold War to its aftermath – the ‘lost decade’ of the 1990s, the ‘War on Drugs’ and the ‘War on Terror’ – as well as some of the major developments and trends related to the extent and nature of foreign participation in the Colombian armed conflict and how these external factors and actors could influence, interact with, or impose themselves upon future events.

Introduction

One of the constants of the social and armed conflict in Colombia since the middle of the twentieth century (with pronounced escalations in the 1960s and again in the 1990s) has been the active participation of US military and intelligence personnel in the planning and implementation of the counter-insurgency strategy and related military and security priorities and objectives. Throughout this period US military ‘advisors’, officials, technicians and a burgeoning number of contractors recruited from throughout the region and beyond have had a permanent presence in Colombia’s most strategic and sensitive military/ intelligence installations and facilities, all the while being protected by an official cover that grants them all of the ‘diplomatic privileges and immunities’ enjoyed by staff of the US Embassy (which is in itself a huge complex equipped to conduct many extraneous intelligence functions).

One of the pivotal features underpinning the many and varied forms of US intervention in the armed conflict has been the clandestine manner in which many of the programs and activities involving foreign military personnel and contractors have been planned and executed. One of the contributions to the Historic Commission (created pursuant to an agreement between the FARC and the Colombian Government to study the origins, causes and nature of the armed conflict) comments in this respect:

“When analysing the causes of the social and armed conflict, as well as the variables that prolonged it and aggravated its impacts on civilian populations, the United States is not merely an external influence but must be considered a direct actor in the conflict due to its prolonged involvement during much of the twentieth century. However, public awareness of the participation of the United States has been deliberately minimized by its covert nature; in accordance with this strategy, many of its activities in Colombia have been ‘planned and executed in such a manner that they can be hidden, or at least enabling plausible deniability of responsibility for such actions.’” (Renan Vega, 2015)

Before considering in more detail the scale, nature, official and covert missions and objectives of the substantial US military/ intelligence presence that has been solidly entrenched in Colombia for many years, it is worth returning to a related topic mentioned in Part I of this report, namely, the determination of the US Government to overthrow the Venezuelan Government, and whether the US might decide to activate a similar set of covert operations against the Colombian Government given the latter’s increasingly independent and forthright posture in international relations.

Preliminary Analysis: A hypothetical case study

Part I mentions a document attributed to ‘South Com’ describing a wide range of alternative strategies, tactics and contingency plans that could be called upon by the US to achieve one of its highest strategic objectives in the region, subjugating or overthrowing the Venezuelan Government. Several of the most extreme measures among the alternatives canvassed refer to a wide range of strategic assets in the region, among which Colombia features prominently (including military and intelligence installations located on Colombian territory, logistics hubs, as well as paramilitary formations and other illegal armed groups that could be recruited or directed to participate in destabilization operations along the border and make incursions into Venezuelan territory to sow terror and possibly carry out assassinations of senior political and military officials). The document is titled “Plan to Overthrow the Venezuelan Dictatorship – ‘Masterstroke’” and really has to be read to be believed (attributed to United States Southern Command, 23 February 2018, the document was first disclosed by a well-known Argentinian investigative journalist, Stella Calloni). LINK

While the possibility of one or more of the extreme types of intervention outlined in the document being activated should not be discounted entirely, it is to be supposed that to the extent that the US, Israel and/ or the UK decide to take direct action against the Colombian Government and President Gustavo Petro, at first they would resort to much more discrete forms of intervention. While there are many other interested and active actors and vested interest groups in Colombia, the presence and capabilities of these three countries – and also Spain – are the most apparent, whether in terms of official military/ intelligence agreements and personnel, the operation and maintenance of the most advanced installations, weapons systems and equipment, or indirectly through private companies, anonymous corporate fronts or other independent contractors.

Such actions would typically include: feeding information and intelligence to media outlets aimed at discrediting and destabilizing the Government; conducting a range of COINTELPRO-type operations against selected target groups and individuals; interrupting supply chains and sharply increasing the price of essential goods and services (‘making the economy scream’); and, ‘exerting maximum pressure’ on the Colombian Government in bilateral and international relations.

Possible tactics and interventions directly targeted at taking advantage of controversial topics and developments peculiar to the current political, social and security conditions in Colombia could include staging ‘false-flag’ incidents and attacks – either against public security forces or civilian targets in order to stoke fear in the public and criticism of the Government’s security strategies, against key infrastructure and facilities to disrupt essential services and functions (possibly disguised to simulate an accident produced by negligence or mismanagement), or against one or more of the illegal armed groups in order to disrupt and discredit the Government’s stated Total Peace project and the numerous associated processes of dialogue and negotiation that have been opened with several of the illegal armed groups.

Another possible course of action would be encouraging the Government’s many political opponents and enemies to support an impeachment resolution or initiate some other political or judicial proceeding in order to weaken and if possible oust the President, strongly supported and uncritically echoed and amplified by most of the mainstream media outlets (almost all of which are owned by hostile critics and opponents of the Petro Government).

A major smear campaign has already been under way for most of the last year, and the vehemence and intensity of the destabilization operation against the Government has steadily increased in scale – along with the degree of coordination or synchronization of forces and activities among disparate political factions and vested interest groups – as time has passed and the Government’s sworn opponents and enemies have become more numerous (as well as desperate and reckless, in their haste to oust Gustavo Petro and retake power over all State institutions and functions as soon as possible).

One of the central components of the destabilization efforts has been undertaken by the Prosecutor General of the Republic (Francisco Barbosa), who has personally directed a veritable inquisition against the President and his family, senior members of the Government, allied political parties and anyone else close to or allied with them, all the while holding loud press conferences to disclose details of ongoing investigations (accompanied by countless insinuations, accusations and suppositions of the guilt of the accused parties while the investigations are still underway) and demanding the President’s resignation or destitution. This performance has been neatly complemented by a constant stream of audio and video footage and other leaks to media outlets that appear to have originated from military/ intelligence sources, or from some other illegal interception and surveillance program(s) being conducted by third parties.

In this context, the question arises as to who could be running a covert and illegal surveillance operation, how, and from whom are they obtaining the intercepted (or fabricated) communications, documents or videos in each instance. As the following analysis will demonstrate, the possible sources are many and varied and include for starters:

- A large and diverse number of Telecommunications Companies and Service providers including: System designers, operators and technicians: Private Security, Intelligence or Technology Companies.

- Military/ intelligence or law enforcement personnel and technical operators, whether Colombian (the Prosecutor General’s office, National Police, military and intelligence agencies all operate or participate in surveillance programs of some type) or from the US, Israel, the UK (all of whom have personnel permanently deployed throughout the county to manage or supervise the tasks and activities of relevant installations and equipment, whether directly or by way of the many private companies involved in the construction, operation and maintenance of military, intelligence and telecommunications facilities, equipment and/ or software).

- Interception or acquisition by other means, or by other third parties.

In Colombia only targeted, individual telecommunications intercepts and surveillance are authorized by law, and the technical capacities and equipment for conducting such activities (known as ‘Esperanza’) have been brought within the responsibility of the Office of the Prosecutor General of the Republic (the agency with primary responsibility for the conduct of criminal investigations). However, the National Police have autonomously acquired the capability to conduct mass interception and monitoring of communications relying on foreign companies for equipment, technicians and in some cases operators (the main platform is known as ‘Puma’).

The overlapping and competing jurisdiction and surveillance platforms complicate oversight of their programs and the possibility of detecting and investigating illegal and unauthorized surveillance programs and activities, at the same time deepening Colombia’s dependence on (and vulnerability to the covert operations and parallel missions of) companies and personnel from the US, Israel and the UK in the performance of key State functions and duties (the numerous military and intelligence systems and programs whose existence has been revealed in media reports or by other sources are considered below).

Two detailed reports by Privacy International (2015, “Shadow State: Surveillance, Law and Order in Colombia, Privacy International”, and “Demand/ Supply: Exposing the surveillance industry in Colombia”) describe the acquisition and operation of telecommunications interception and monitoring systems by Colombia’s law enforcement and criminal investigation agencies, including the specific companies and technical systems that have been deployed. The report’s findings include the following:

“Over the past decade, the Colombian government has primarily looked to private companies locally, as well as companies in the UK, the US and Israel, to supply surveillance equipment. These companies have provided technologies that enable both network surveillance (the monitoring of communications data and content from service providers’ networks) and tactical surveillance (the monitoring of communications data and content wirelessly or from targeted devices).”

More specifically, the key findings concerning the central features and components of the surveillance and interception systems that have been established include the following:

“This investigation finds that the national police, intelligence and security services were and are capable of carrying out interception on a massive scale outside of the existing Colombian legal framework. Rivalries between different law enforcement and intelligence agencies, each operating with different budgets and legal mandates, create a situation in which Colombians’ communications traffic is being passively collected by different uncoordinated and often competing surveillance systems. An overly broad, technically unsound legal framework enables interception of communications to occur without adequate safeguards…

The most notorious of the interception scandals involves the DAS (Department of Administrative Security) and was revealed by Semana in February 2009. Secret strategic intelligence groups formed within the DAS conducted targeted surveillance of an estimated 600 public figures including parliamentarians, journalists, human rights activists, lawyers and judges, among others. According to files retrieved during an investigation by the Fiscalía (Office of the Prosecutor General), the DAS intercepted phone calls, email traffic and international and national contacts lists, using this information to compile psychological profiles of targets and conduct physical surveillance of the subjects, their families and even their children.

Communications surveillance was central to the DAS abuses… Such was the scale of the illegal interception that seven Supreme Court justices were recused from the 2011 trial of the former DAS head because evidence suggested that they had been illegally spied on…

[Following the succession of major public scandals the DAS was abolished in 2011. The intelligence and counterintelligence functions performed by DAS were taken over by the newly created National Intelligence Directorate (Dirección Nacional de Inteligencia) or transferred to other agencies – or outsourced, presumably.]

Fiscalía officials met with US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) officials in the early 2000s to develop the system, originally established in 2004 as ‘Project Esperanza’ and formalized in 2005 by Inter-Administrative Agreement 038 of 2005 as a joint interception system of the Fiscalía, Police and DAS.

Interception through Esperanza involves capturing individuals’ communications on a targeted basis, with the knowledge and cooperation of the telecommunications service provider, and is explicitly authorised under Colombian law… Esperanza was connected to at least 20 rooms in 2012 identified by colours. At least six of these rooms received financial and technical support from the DEA, and DEA analysts share workspace with their Colombian colleagues. The US embassy is metres away from the operations centre…

Esperanza has not always worked as planned. By mid-2009, connections between the rooms were routinely breaking down. Police and DAS officials submitted panicked messages requesting help… STAR engineers [STAR Inteligencia y Tecnología is a Colombian-registered company that is the exclusive representative in Colombia for several security and intelligence products provided by British and US companies] made dozens of visits to DAS monitoring rooms in 2009 and 2010 to fix problems and make improvements to the platforms on which data intercepted in the Esperanza system was analysed. Despite Esperanza’s numerous known technical faults and the revelations about the DAS’ illegal surveillance of journalists, activists and public officials that had been publicly known since 2008, Esperanza’s capacities have been continually expanded…

Meanwhile, the PUMA surveillance and interception platform (Single Monitoring and Analysis Platform – Plataforma Única de Monitoreo y Análisis) relies on technologies significantly more powerful and invasive than those of Esperanza… PUMA is capable of intercepting and potentially storing all communications transmitted on the high-volume cables that make up the backbone on which all Colombians rely to speak to and message each other…

After the Police concluded the initial contracts with Compañía Comercial Curacao de Colombia (‘La Curacao’), the legal representative and only authorized distributor for Verint Systems in Colombia, Verint engineers placed 16 ‘IP-PROBER’ probes on the trunk lines. Service providers knew of their existence and helped to install the connections but were not involved in their day-to-day operation, according to former Verint employees.

The probes intercept data and send it back to PUMA monitoring centres. La Curacao won subsequent contracts to install and maintain PUMA’s hardware and software from 2008 to 2013. La Curacao engineers were vetted by DIPOL (the Directorate of Police Intelligence) and maintained the monitoring centres’ data centre, servers and data storage racks. They even updated administrator passwords on PUMA servers in 2011.”

The Nature and Extent of US Participation in the Colombian Conflict

From relatively modest beginnings, the direct and indirect military/ intelligence and advisory/ supervisory (command, control and capacitation) roles of the United States in the armed conflict in Colombia has only increased over time. At the same time, the scope of the ‘diplomatic immunities and privileges’ from all Colombian laws and jurisdiction included in the relevant bilateral agreements has been steadily expanded to include not only all military personnel deployed pursuant to the bilateral agreements but also all contractors as well as, since 2003, a purported exclusion from the ambit and jurisdiction of international law and the International Criminal Court.

While many other military/ intelligence programs and activities existed previously (such as direct deployments of military officials, delegations and units, weapons exports, frequent military exercises and missions and in-country training programs, as well as the notorious School of the Americas – at which the Colombian military delegation has always been one of the largest), the formal announcement of ‘Plan Colombia’ in 2000 dramatically escalated the direct US military/ intelligence presence in Colombia as well as the scale and destructiveness of the ‘War on Drugs’, and before long it had morphed into a massive and open-ended mission pursuing a diverse and vaguely defined range of objectives and tasks:

Before the attacks on the 11th of September 2001 in New York (and the subsequent declaration of a ‘Global war on Terror’ by the Bush administration), the Colombian guerrilla groups were considered belligerent armed political forces. From that moment on the Department of State began to call them ‘terrorist’ organizations. In 2002, the US Congress approved an increase in the number of special forces troops sent to Colombia … (and) authorized the use of the US military’s ‘anti-narcotics’ capabilities in Colombia to support counter-insurgency operations. Such support also implied the involvement of subcontractors and PMCs.

In reality, Washington has stopped trying to find excuses and has made official what has always been the case. This change that consecrated continuity has a name – Plan Patriota – and also signals a fundamental readjustment of the priorities and focal points of the war, shifting them to the petroleum zones near the Venezuelan border…

When it approved Plan Colombia in 2000, the US Congress authorized not just the presence of (400) military personnel, but also up to 400 civilian ‘contractors’ (increased to 800 military personnel and 600 contractors in 2002), numerical limitations that subsequently would easily be exceeded. As the law only mentioned contractors from the United States, the Department of State and companies like DynCorp contracted people from Guatemala, Honduras or Peru, thereby tranquilly surpassing the established limit. In practice, Plan Colombia merely legalized activities that several of these companies were already undertaking… (Calvo Ospina, 2004)

One of the contributions to the Historic Commission argues of the bilateral relationship that has been systematically crafted and consolidated over many decades:

These actions (bilateral military agreements and cooperation) are carried out within a relationship of subordination, understood as a relationship of dependency in which the national interests of Colombia have been placed at the service of a third party (the United States), which is perceived as being endowed with political, economic, cultural and moral superiority. It is an unequal and asymmetrical relationship that has assumed a strategic character, as the very existence of the Colombian Republic is thought to be inextricably linked to its condition of subordination to the United States, due to which it is more appropriate to speak of a strategic rather than a pragmatic subordination….

Understood as ‘subordination by invitation’, the relations between the United States and Colombia require an examination of the roles and motives of the people in power who have maintained the condition of dependency. One significant aspect of the relationships that have developed over time is that “there has been a pact between the national elites for more than one hundred years, for whom this subordination has produced economic and political benefits.” These benefits are administered through practices of patronage that permeate all of the political and social institutions and structures in Colombia. The utilization of patronage through international networks and relations is readily apparent in all sectors of the State, the Army and the Police, for whom the foreign support and the military budget are private bounties that can grant them great power and privilege in their dealings with colleagues and rivals…

Strategic subordination and restricted autonomy are also keys to understanding the duration of the conflict, because it is impossible to ignore the absolute centrality of the United States in the definition of the political lines that the power elite in Colombia have adopted; from the anti-communism of the Cold War to the “War on Drugs” and the “Global War on Terror”. In each case Washington has provided Colombia’s political and military elite with the arguments and the agenda… (Renan Vega Cantor, 2015)

This core US strategic objective – establishing and maintaining a condition of strategic subordination among its international ‘allies’ and ‘partners’ – is of course replicated in its bilateral relations with all other countries in the region, complemented by a wide range of parallel measures and techniques that have been developed over time to prevent the creation and growth of independent bilateral, regional and international political alliances and economic cooperation by the Latin American countries among themselves. As argued by Socorro Ramirez (2004), the systematic cultivation of asymmetrical bilateral and regional relations based on the fundamental premise of maintaining political, economic, military and technological superiority and regional adherence to and support of the strategic interests of the United States has been greatly facilitated by the tendency of the traditional ruling classes in each country to view relations with their neighbours in zero sum terms:

“Far from seeking to establish a joint response to the Colombian conflict, each of the neighbouring countries have limited their actions to protecting themselves and denouncing the external impacts of the conflict… Expecting a different attitude from their governments and politicians is unrealistic, as each country is faced with its own deep-seated problems which tend to prevent international solidarity and cooperation, such as economic instability, political uncertainty, poverty and social turbulence. These factors have all contributed to the fragmentation of their societies, the weakness of State institutions, and the further reduction of their already limited margins for international cooperation… In this broader context, each country has tried to transfer the impacts of its own problems to its nearest neighbours. Rather than supporting their counterparts in the region or trying to find common solutions to situations that affect them all, the difficulties of others are perceived as an opportunity to be used in their relations with competitors and rivals…

Moreover, in terms of topics and activities of shared concern – such as drug trafficking – each country is implicated and affected differently and has distinct interests and perspectives; there are few loyalties in their dealings with historic economic and military rivals… Above all, the United States continues to be the priority economic and political partner of all of the Andean countries, which limits the possibilities for meaningful cooperation between them in order to resolve their common problems or establish a common regional and international strategy.”

By the late 1990s the United States had succeeded in imposing its political, military and economic hegemony over the entire Latin American region, with the stubborn exception of Cuba. However, in the years following the election of Hugo Chavez in Venezuela in 1998 the governments of many countries throughout the region have re-asserted their independence and sovereignty, both in the determination of national economic, political and military matters as well as in their international relations, giving rise to what many people in the region consider to be nothing less than a second War of Independence (Hector Bernardo, 2018).

Prior to Hugo Chavez’ presidency Venezuela, Colombia and Ecuador had all been firmly within the US ‘orbit’ for many years. Even during this extended period, however, bilateral economic, political and technological relations and cooperation between them had been minimal notwithstanding their common ideological and geopolitical alignments. Although Venezuela and Ecuador established a strategic partnership between 2007 and the around 2017 (during the presidency of Rafael Correa), forming part of the nucleus of the rejuvenated independence movement throughout the continent, their attempts to forge closer economic and political links were thwarted for the most part by the logistical difficulties as they do not share a common border. Very little major infrastructure has been constructed to provide connectivity between the neighbouring countries, and major bulk transport networks and links remain almost non-existent. Meanwhile, Colombia was one of the US’ most stoic ‘allies’ throughout this period, guaranteeing very tense and difficult relations with both countries (there were frequent border skirmishes and incursions involving a confused mix of conventional forces and illegal armed groups in several conflict and crime-infested border zones, and around 2010 it seemed possible that Venezuela and Colombia might go to war as the war of words between Hugo Chavez and Álvaro Uribe reached crisis point).

One of the biggest dilemmas of the Colombian and US governments during these volatile border clashes and heated confrontations was the complete inadequacy of the Colombian armed forces in terms of conducting offensive operations and defending against a well-armed external threat or enemy. The Colombian armed forces have been structured, equipped and trained pursuant to the overriding requirements and objectives of the Counter-Insurgency Doctrine. One of the consequences is that almost all of its weapons are aimed at and used against vast sectors of the Colombian people – designated actual or suspected ‘internal enemies’ – rather than being acquired and deployed for the purpose of defending the country against external attack by a well-armed enemy. Nor do the armed forces possess advanced heavy weapons systems capable of launching and sustaining an attack into foreign territory (unlike Brazil, Chile or Peru in particular, though Venezuela has made major gains in terms of its strategic military doctrines and capabilities over the last twenty years).

In terms of the role of the US military in this broader geopolitical context, there is a significant permanent presence in most countries throughout the region, supplemented by regular training programs and frequent military exercises that enable much larger numbers of US military personnel and experts to become familiar with operating conditions in each country as well as providing a deep knowledge and understanding of each country’s respective military capabilities and weaknesses. In most cases the people, the national Congress and even the armed forces and Government of the ‘host country’ involved have no idea of exactly how many foreign military personnel and contractors have been deployed in the country or of what they are doing.

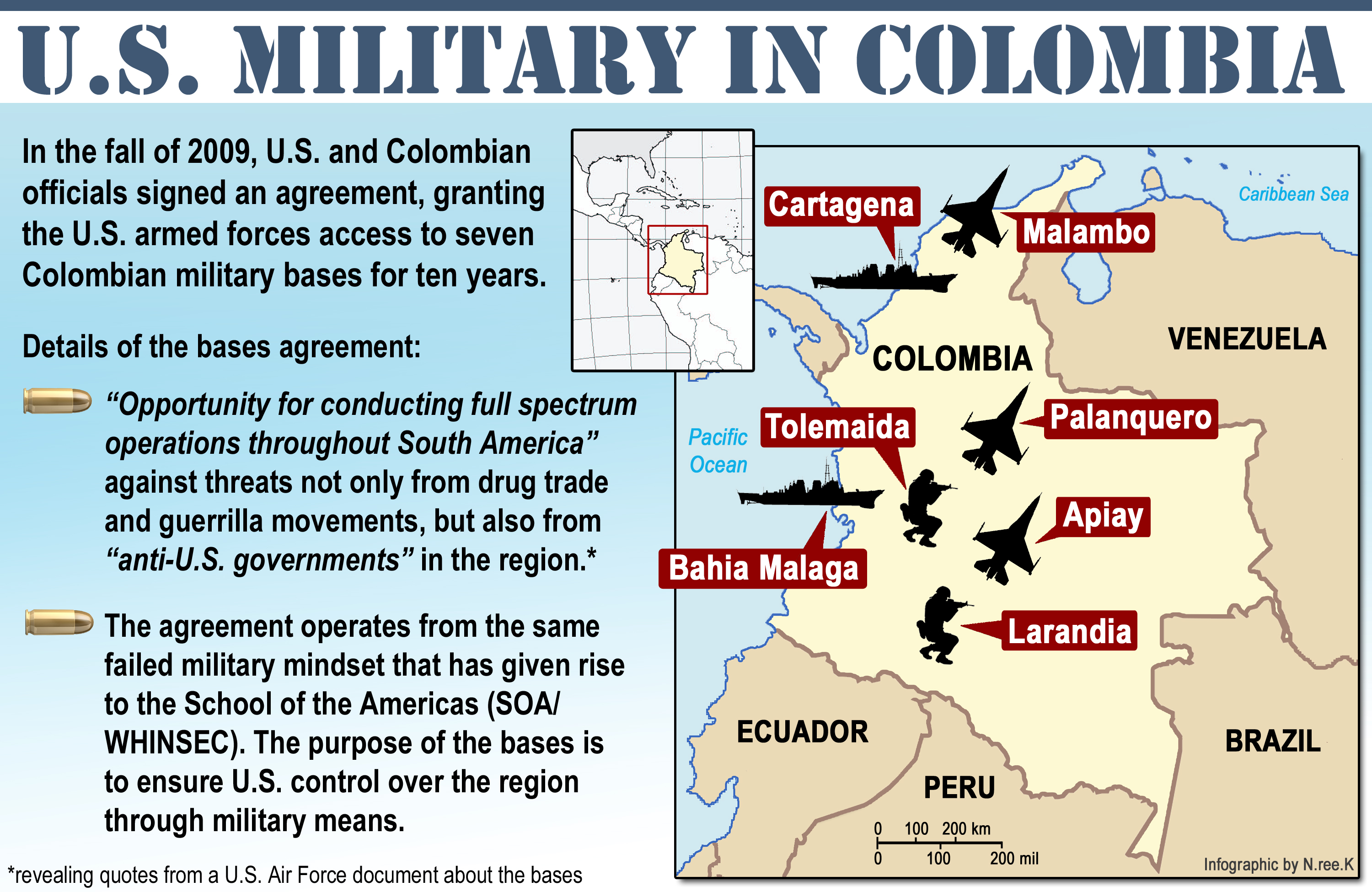

In the course of legal proceedings related to a petition contesting the validity of a bilateral military agreement signed in 2009 (Auto 288/ 2010), the Constitutional Court examined the extent of the US military presence on Colombian territory and some of the implications and consequences for Colombia’s sovereignty. Among many other pertinent comments and observations, the Court noted that the commitments purportedly undertaken by Colombia pursuant to the agreement signed by the Uribe administration:

“are of transcendental significance due to their connection with diverse topics related to the political-constitutional order such as, among others, the exercise of sovereignty, the restrictions on the punitive powers of the State, the status of personnel, the principle of fiscal sovereignty, the monopoly over the use of force, and eminent dominion over the territory as constitutive elements of the State…

[In this respect, the accord contains the following commitments, among others.] Authorization to enter and utilize military installations by foreign military and civilian personnel. The Accord of 2009 permits the United States unrestricted access and use, with permanent vocation, to the Air Force Base Germán Olano Moreno (Palanquero), the Air Force Base Alberto Pawells Rodríguez (Malambo), the Military Fort of Tolemaida (Nilo), the Military Fort Larandia (Florencia), the Air Force Base Capitán Luis Fernando Gómez Niño (Apíay), the Naval Base ARC Bolívar in Cartagena and the Naval Base ARC Málaga in Bahía Málaga, as well as such others as may be agreed between the parties…

Access to and free circulation in the agreed installations by United States personnel… Faculty of entry and free circulation of foreign ships, vehicles, aircraft and tactical vehicles in the national territory, without possibility of inspection or control by the national authorities… Authorization to bear and use arms in the national territory by foreign personnel… Recognition and amplification of a personal statute of diplomatic and fiscal immunities and privileges for personnel, contractors and subcontractors of the United States… ”

Moreover, other provisions of the Accord provide that:

“The Colombian State authorizes the United States to establish satellite receiving stations for radio and television transmissions, without licence applications and without cost… The Colombian State authorizes the United States to utilize the infrastructure of the telecommunications network as required (radio frequencies and the electromagnetic spectrum) to achieve the objectives of the Accord, without application processes or licence concessions and without cost…” (Translation by the author.)

These latter provisions would include the many advanced intelligence, radar and surveillance installations built by the United States military or private contractors in strategic locations throughout the country to conduct surveillance and interception operations covering the country’s land, airspace, maritime zones and telecommunications networks. Moreover, it must be added that the list of military installations and zones mentioned in these official documents is far from comprehensive. They represent the main permanent deployments of substantial numbers of personnel to key strategic points and operating bases. There are also innumerable smaller permanent deployments or temporary covert missions and operations throughout Colombian territory, complemented by the ubiquitous presence of USAID in many regional State institutions and municipalities of high strategic value.

As other investigations into the extensive and multi-faceted US participation in the Colombian conflict make clear, there are many such installations and systems responsible for strategic tasks and functions that have been established and that continue to be maintained and operated by US companies and other contractors, mostly from the UK and Israel, in close collaboration with and generally subject to direction and supervision by US officials.

Alongside the official US military deployments and missions to Colombia, and rivalling them in terms of their scale and strategic significance, a large number of private companies (mostly from the US, UK and Israel) have been delegated responsibility for the construction and management of advanced military/ intelligence installations, equipment and tasks throughout the country. For example, a summary of such projects as of 2004 included the following:

Lockheed Martin offers – among other services – technical assistance to maintain the combat helicopters and aircraft for transporting troops. Northrop Grumman installed and manages seven powerful radar systems, coordinated with a sophisticated aerial surveillance and espionage system. This company also trains military personnel and paramilitaries for ‘special operations’. Other firms such as MariTech, TRW, Matcom and Alion utilize advanced technologies to take photographs from space, intercept communications, and analyse the data obtained. This information is transmitted to the Surveillance System of the US Army´s South Command (Southcom) and the CIA, which review the information and redistribute it as they see fit. The Colombian armed forces are usually the last to be informed…

Meanwhile, the US military and Embassy have made full use of the provisions conferring diplomatic privileges and immunities, hastily withdrawing from Colombia and redeploying any US military personnel or contractors accused of criminal conduct and refusing to cooperate with Colombian authorities on the few occasions when they have attempted to investigate such criminal activities.

The Origins of the Counter-Insurgency Doctrine and the Paramilitary Strategy

One of the major contributions of the US to the intensification, prolongation and barbarity of the armed conflict has been overseeing the refinement and expansion of one of the pillars of the governments’ campaign against armed insurgent groups, the Counter-Insurgency Doctrine and Paramilitary Strategy. In the official report of the Historic Commission on the conflict in Colombia and its victims (published in 2015) one of the chapters describes in detail the instrumental role of the US military in the modernization of the Colombian Establishment’s traditional strategies used to preserve their privileges and prevent the formation of opposition political parties or social movements.

Up until the 1960s these techniques were based in part on the creation of a variety of semi-official, mixed or private militia formations (usually as partisans of the ruling Liberal and Conservative parties in their fratricidal disputes for control over the State’s institutions, powers and resources), often involving armed militias comprising both individuals from regional military or police units as well as partisan civilians whose members would operate in varying degrees of cooperation with elements of the State’s regular armed forces, intelligence and police forces. According to one description of the origins and evolution of the paramilitary phenomenon in Colombia:

The formation of paramilitary forces was itself preceded by the creation of private militias at the service of large landowners in the late 1940s and early 1950s that ravaged the countryside during ‘the Violence’ (a brutal civil war marked by widespread indiscriminate massacres in rural areas that claimed over 200,000 victims and displaced millions of people from some of the most fertile regions, lands that were rapidly occupied and incorporated into large landholdings by the political and economic elites)…

The prolongation of the paramilitary strategy over time and the role that it has played in the neoliberal era – violently displacing rural communities and taking over their land for agricultural, mining, energy and infrastructure mega-projects or to extend the domains of large cattle ranches – signified the construction of a para-State to exercise dominion over large swathes of the territory and State institutions.

While it may well be that the paramilitary armies no longer receive orders directly from the government, that doesn’t mean that substantial sectors within the military establishment and other State institutions don´t still consider them to be allies in the fight against the armed insurgent groups and therefore continue supporting them and maintaining the relationships that developed over a long period of time. Considered in these terms, paramilitarism isn’t simply a group of criminal gangs that has managed to infiltrate and subvert State institutions but rather represents a continuation of the basic features and components of the para-State.

The ongoing assassination of human rights defenders, farmers and militants of the political opposition in the country constitutes the maintenance of the same pattern of extermination practiced over the preceding decades, varying in degree and intensity in different periods but always following the same methodology and objectives as outlined by the doctrine of National Security: anti-communism…

Giraldo describes the essence of this doctrine as follows: “In the arsenal of the doctrine of National Security – fundamentally comprising books (in the Library of the National Army), editorials and articles appearing in the Journal of the Armed Forces and in the Journal of the Army, discourses, presentations and reports of high level military commanders and their advisors, as well as in a collection of Counter-Insurgency Manuals marked as secret or confidential – ‘communists’ are explicitly identified as trade unionists, farmers who are reluctant to cooperate with military operations on their properties, students that participate in street protests, leaders and militants of non-traditional political factions, human rights defenders, proponents of liberation theology, and other social movements and sectors that are not in conformity with the status quo…” (José Honorio Martinez, 2016)

Following the formation of the National Front (an agreement reached in 1956 pursuant to which the Liberals and Conservatives agreed to share power between themselves, while at the same time excluding all other political parties), the techniques were modified to focus exclusively on crushing any opposition to their joint hegemony over the State:

“The counterinsurgency strategy of the State has been founded upon paramilitarism. The official version of the phenomenon places its origin in the 1980s and explains it as arising from the reaction of rural land owners and agricultural and business associations to confront guerrilla actions, in response to which the land owners and businessmen in rural areas decided to create private armies to defend themselves, from which came the name commonly used to refer to such groups, ‘self-defence forces’. This remains the essence of the official version today.

However, the real origin of the paramilitary strategy, as proven by official documents, can be traced back to the Yarborough Mission, an official mission to Colombia by officials of the Special Warfare College of Fort Bragg (North Carolina) in February 1962. The members of the commission left a secret document, accompanied by an ultra-secret annex, containing instructions for the formation of mixed groups of civilians and military personnel, trained in secret to be utilized in the event that the national security situation were to deteriorate…”

Brigadier General William P. Yarborough, Commander, U.S. Army Special Warfare Center (SWC), Fort Bragg, North Carolina, accompanied by 7th Special Forces Group (SFG) commander, COL Clyde R. Russell, and LTC John T. Little, G-3, SWC, visited Colombia from 2–13 February 1962.

It is worth quoting passages from two other well-informed studies of the Paramilitary phenomenon that provide further corroboration of the preceding findings and conclusions:

“Detailed evidence about the links between paramilitaries and the public security forces have been presented in works such as those of Carlos Medina Gallego (1990) Autodefensas, paramilitares y narcotráfico en Colombia; Mauricio Romero (2003) Paramilitares y autodefensas, and the study conducted by Corporación Nuevo Arco Iris titled Parapolítica. Moreover, for several years even the national press has announced that following the para-politics scandal (in which State prosecutors and magistrates have conducted a substantial number of investigations of politicians linked to paramilitarism), a similar process took place relating to the army, the Police and other security agencies. The news magazine Semana affirmed at the time: ‘The Pandora’s box is starting to open concerning the nexus between the military and the self-defence forces, and it could be worse than the para-politics. Would that be possible? Is it convenient in the middle of the war?’” … (Vega Vargas and Ó Loingsigh, 2010)

“Since the 1980s, political bosses from regions beyond the capital – many of them large landholders with ties to narcotrafficking – fostered and funded brutal pro-government paramilitary groups. These militias’ scorched earth tactics killed tens of thousands of non-combatants in the 1990s and early 2000s. The paramilitaries’ onslaught, marked by hundreds of gruesome massacres and mass graves, caused them to surpass the guerrillas and the armed forces as Colombia’s worst human rights violators.

However, the paramilitaries could not have functioned and prospered without support from the politicians who held local power. Evidence, much of it from former paramilitary leaders, has brought a cascade of criminal investigations of legislators, governors, mayors and other officials, who made common cause with the far-right warlords…

As of November 2009, of the 268 congress people and senators elected in 2006: 43 were under official investigation, 13 were on trial, and 12 had been convicted for parapolitics. This total (68) is equivalent to 25% of the entire Congress. Eight were opposition legislators; the remaining 60 made up about 38% of the entire pro-government bloc…

[Around the same time as the extent of the para-politics corruption and collusion was becoming apparent, there were] waves of allegations of criminal activity, collusion with paramilitaries, illegal surveillance and intimidation carried out by the Administrative Department for Security (DAS), the Colombian Presidency’s intelligence service or secret police. This troubled agency, a long-time U.S. aid recipient, appears to have been wildly out of control and used for evil purposes, severely undermining the Colombian government’s security gains.

President Uribe’s first DAS director, Jorge Noguera, allegedly shared information about military operations with the AUC paramilitaries’ Northern Bloc, among other paramilitary and narcotrafficking organizations. This included giving the paramilitaries lists of labor leaders, human rights defenders and other opposition figures to kill; some of those orders were brutally carried out. Today, Jorge Noguera, who served over three years as chief of presidential intelligence, is on trial for aggravated homicide.

Noguera’s departure did not end the problems at the DAS. In early 2009 Colombians were scandalized by new revelations that the security agency carried out a campaign of wiretaps and surveillance against dozens of human rights defenders, independent journalists, opposition politicians and even Supreme Court justices, especially those investigating ‘parapolitics’.” (Isaacson, 2010)

In terms of the central role of the US in the Paramilitary phenomenon, and the planning and execution of the counter-insurgency doctrine and associated campaigns of State terror more generally:

“In spite of the widely documented denunciations of collusion between certain Army and Police units and paramilitary groups throughout the 1990s the level of US military assistance continued to increase significantly, culminating in Plan Colombia… According to the Institute of Political Studies in the United States, “everything indicates that the support provided by the CIA and the Special Forces of the United States to the paramilitary groups was one of the factors that enabled them to consolidate their forces in a way that had not been possible before.” (Vega Cantor, 2015)

The central role of the US military in planning and executing the military dimensions of the Paramilitary Strategy was reinforced by its oversight and direction of Colombia’s national intelligence agency:

The DAS (Department of Administrative Security, the national intelligence agency) was created in 1960 to replace the previous intelligence agency (the SIC), in accordance with the proposal of the military mission that visited Colombia in 1959 to convert the agency into an entity effectively under the control of the United States to conduct counter-insurgency operations.

The measures adopted by the US to secure control over intelligence operations in Colombia extended to recruiting and infiltrating agents into all spheres of Colombian society, as revealed by a 1964 document sent from the us Embassy and USAID to Colombian President Guillermo León Valencia. Hundreds of declassified documents from the CIA, USAID and the US Embassy reveal that they followed the evolution of the DAS very closely, training its officials and providing equipment and technical assistance…

During the administration of Úribe Veléz (2002-2010) the DAS organized a criminal scheme to assassinate government opponents and trade unionists, facilitated by an alliance between its Director (Jorge Noguera) and paramilitary groups… At the same time, the “chuzadas” became general practice, a euphemism referring to the illegal interception of the communications of political opponents, NGOs and members of the Supreme Court…

Early in 2014 a new scandal erupted with the so-called Operation Andromeda, pursuant to which the Army spied on the negotiations between the Colombian government and the FARC in Cuba… In this instance, it was subsequently revealed that in the Centre of Military Intelligence and Counter-Intelligence (CIME) of the Colombian Armed Forces there is a ‘grey room’ where illegal intercepts are carried out, producing information which can then be used to harass, intimidate or even assassinate people. According to a military official who has worked in the unit, the CIA “supplied economic and technical support so that the room could operate. Everything, absolutely everything that happens there is known by them. They know all of the details as to what, against whom and why the espionage and intercepts are carried out in the room. In practical terms, they are the real bosses of what happens there.”

These delicate facts, which were reported and then rapidly forgotten, are just a small sample of the corrupt and deceptive activities being carried out by the United States and Colombia, and provide some indication of the possible risks and dangers posed by the control that US intelligence services have over Colombian intelligence and security agencies. It is not a matter of the DAS deviating from its official functions with the passage of time to end up becoming involved in dubious and illegal activities; the agency was created as an instrument designed to carry out “open and disguised psychological warfare”, as stated by the report of the military mission from the United States in 1959…” (Vega Cantor, 2015)

Apart from their burgeoning direct role in the military, intelligence and security sectors and the planning and conduct of counter-insurgency and anti-narcotics operations, a significant number of foreign companies have also fueled and participated in the armed conflict in many other ways. Reported activities include organizing large clandestine weapon shipments to the paramilitary groups and hosting training camps, logistical bases and transport hubs for military, intelligence and paramilitary operations on their properties. The first instalment of this report includes details of the direct involvement of Chiquita Brands in the importation of military-grade weapons for the paramilitary formations, including thousands of automatic rifles and millions of rounds of ammunition.

As one of many other possible illustrations, a detailed analysis of the development of BP’s petroleum project in Casanare (in the north-west of the country) documents the many ways in which the company facilitated and benefited from the implementation of the Paramilitary Strategy in the region surrounding the company’s production facilities, at the same time cautioning that:

[The investigations and judicial] sentences that have implicated companies such as Chiquita Brands in the financing of paramilitary groups can be understood as supporting the argument that connects the implantation of transnational capital in Colombia with the phenomena of violence and the conduct of the dirty war. But the relationship between transnationals and the violence is not always so easy to prove. The companies’ involvement is often intermediated through a series of secret contracts and agreements with a State that often behaves more as the administrator of a mode of accumulation that benefits these companies than as a guarantor of the rights of its citizens… (Vega Vargas and Ó Loingsigh, 2010)

Another report states of the rapid expansion and diversification of the direct forms of participation of several foreign petroleum companies in the armed conflict in Colombia since the 1990s:

The guerrillas were obstructing the production and transportation of petroleum, considering that this activity only benefited the multinationals and a small number of Colombians. The first company known to have utilized mercenaries to protect its infrastructure was Texaco. In 1997 and 1998 the British company Defence Systems Ltd collaborated with the Colombian army, at the same time as it was training paramilitaries on behalf of British Petroleum, Total and Triton, resorting to the Israeli firm Silver Shadow to acquire arms… [Around the same time, one of Occidental Petroleum’s properties was also being used as a logistics base and staging ground for PMCs conducting aerial narcotics and counter-insurgency surveillance operations.] (Hernando Calvo Ospina, 2004)

The investigation by Hernando Calvo Ospin provides details of several other instances in which foreign companies have been implicated in directly, knowingly – and clandestinely – supporting the activities of paramilitary formations and benefiting from the atrocities and crimes against humanity that some of them committed:

In 1987, under the approving gaze of the Government, large rural landowners and drug traffickers linked to the Medellín cartel secured the services of the Israeli security company Hod He`Hanitin (Spearhead Ltd) to train paramilitaries. Some of the training programs were realized at installations and properties owned by Texas Petroleum Co. and were directed by ex-officials of the Israeli army and Mossad – such as lieutenant colonel Yair Klein – and former members of the British SAS.

These mercenaries taught ‘anti-subversive techniques’ that would then be used to ‘cleanse’ the banana plantation and petroleum zones, eliminating people suspected of supporting the guerrillas. Between 1987 and 1992, the skills taught at the training camps were also used to carry out the assassinations of Jaime Pardo Leal and Bernardo Jaramillo (Union Patriótica), Carlos Pizarro (M-19) and Luis Carlos Galán (Liberal), all of whom were presidential candidates opposed to the Establishment.

According to a report by the special rapporteur of the United Nations presented to the Human Rights Commission in February 1990, more than 140 paramilitary groups were operating in Colombia at the time in close collaboration with the army and the national police. These militias attacked not only guerrilla sympathizers, but also workers, trade unionists and farmers who had nothing to do with the guerrilla groups, causing thousands of victims.

The term ‘paramilitary’ was frequently utilized as a point of reference, employed in a euphemistic manner in order to hide the role of the army and the political forces promoting the campaign of extermination. By waging a ‘dirty war’ instead of conventional military operations by the armed forces, the paramilitary groups enabled the military and politicians to refurbish their public image and to thereby aspire to obtaining increased assistance from the US, assistance that had been substantially reduced due to the persistent human rights violations…

The Persistence of the Counter-Insurgency Doctrine and the Paramilitary Strategy: Geopolitical, Strategic and Institutional Inertia

Several accounts describing the origins, motives, objectives, modus operandi and main actors involved in the planning and execution of the Paramilitary Strategy over successive periods were outlined above. More recently, a report jointly produced by a group of prominent civil society organizations (Mesa Nacional de Garantías, 2018) adds further testimony concerning the continuity of the paramilitary-based counterinsurgency doctrine notwithstanding the official endorsement of the peace process by the Colombian State following the signing of the Final Accord with the FARC insurgent group in 2016:

“[The Minister of Defence and] the Prosecutor General of the Nation have taken a posture that tries to deny the systematic nature of the attacks against defenders of human rights by the paramilitary structures. Until recently the Prosecutor General repeatedly stated to the media that ‘there is no systematic strategy behind the assassinations of human rights defenders…’

The State continues to deny the existence of paramilitary groups and since 2006 has baptized them with names that disguise their political character and the links that these groups have with State institutions and actors; Criminal Bands (BACRIM) or Organized Armed Groups (GAOs). The Minister [of Defence] has repeatedly declared that – ‘In Colombia paramilitarism doesn’t exist. To say that there is paramilitarism in Colombia would be to grant political recognition to some bandits dedicated to common or organized delinquency’ – failing to acknowledge the paternity that the State has in the creation and maintenance of the paramilitary structures, favouring their creation in accordance with distinct military manuals related to combatting guerrillas and the counterinsurgency doctrine of the State.

The Paramilitary phenomenon is one part of a broader State policy anchored in the doctrine of national security, which establishes as one of the core counterinsurgency strategies the targeting and persecution of social movements, political opponents, social leaders and human rights defenders, all of whom are referred to as internal enemies and equated with the guerrilla groups. On this fundamental premise the targeted social sectors and groups are stigmatized, persecuted and attacked. It is disturbing for civil society organizations that in spite of the Peace Accord, the counter-insurgency doctrine is still in place and has not been modified, that it continues justifying and naturalizing attacks against the social and human rights movements…

The persistence of the paramilitary phenomenon can be explained by four elements; first, not all of the paramilitary groups demobilized. Second, the results of the demobilization were not effective partly due to the fact that the demobilization was not simultaneous. Third, many mid-level commanders did not take part in the process and continued their criminal activities. Finally, the financers and third party beneficiaries of the paramilitary groups’ activities were not investigated: many of their structures remained intact in the regions following the demobilization and still have not been identified and dismantled, notwithstanding the most recent legislation which gives them the option of participating ‘voluntarily’ (in the JEP war crimes tribunal proceedings) given that the ordinary justice system hasn’t done anything and nothing indicates that it will…

An investigation by the Colombian Commission of Jurists published in 2010 also provides detailed evidence and testimony concerning the continuity and ongoing reliance on the paramilitary strategy by powerful sectors and groups, emphasizing that the profile of the victims of systematic selective assassinations and terrorization has not changed nor have the methods of the perpetrators, while at the same time many State officials and media outlets have consistently denied that such a strategy even exists. On this aspect of the armed conflict the report by the Colombian Commission of Jurists comments:

“The ongoing violations of the right to life demonstrate that unfortunately the paramilitary groups continue to exist and that they continue committing violations against human rights with the same patterns of violence targeting the same sectors or groups of society that have been under attack since the origin of the conflict. No changes have been registered in the methods and patterns of the attacks, nor has there been a change in the profile of the victims which would permit us to affirm that the current forms of violence are distinct from those traditionally used by the paramilitary groups. The principal characteristics of the commissioning of violations of the right to life have been maintained and they are being committed as a means of social and political persecution and in order to sow terror amongst the civilian population…

The violations of the right to life committed by the paramilitary groups are of a selective nature and many of them have been committed against people who have attained roles of leadership in society and local communities, such as political leaders, trade unionists, and human rights defenders. The paramilitary groups also systematically attack vulnerable sectors of the community, such as women, children, Indigenous people, Afro-Colombians, farmers and rural communities, people who have been forcibly displaced and other marginalised groups…”

Meanwhile, the report “¡BASTA YA!” (Grupo de Memoria Histórica, 2013) remains one of the most rigorously investigated and well-documented overviews of the origins and nature of the armed conflict, the multiple impacts it has had on the most vulnerable social sectors, the perpetrators of the violence, their motives and objectives, as well as characteristic types or classes of military/ paramilitary/ guerrilla/ ‘criminal band’ (‘BACRIM’) operations and tactics, and identifiable patterns of violence used in different regions or against specific social sectors, groups and individuals.

President Juan Manuel Santos, front left, and Rodrigo Londoño, the top rebel commander, at a signing ceremony in Cartagena, Colombia.Credit…Fernando Vergara/Associated Press

One of the key provisions of the Peace Accord that finally persuaded the FARC to surrender their weapons, demobilize and participate in a transition plan aimed at their reintegration into society was a commitment to identify and dismantle the paramilitary structures that have become increasingly intertwined with the country’s military, security, political and economic institutions over the last forty years. This remains one of the greatest challenges to finding a lasting solution to the armed conflict in Colombia.

Most of the political and military officials directing Colombia’s military/ intelligence apparatus and public security forces over time have never explicitly acknowledged their deep involvement in the creation and proliferation of – or at the least tacit collaboration with – many of the paramilitary and other illegal armed groups (including many of the most powerful drug cartels that have appeared and vanished over time, the void left by the annihilation of one cartel always being quickly filled by some other group), or the decisive behind-the-scenes role played by the United States, and to a lesser but still very substantial extent Israel and the United Kingdom, along with a horde of private companies and contractors most of which are based in or controlled from those three countries.

As far as I am aware, this remains the official position of the Colombian State today (and of course the US Government): Deny, Deny, Deny. In this sense, a most urgent task is the conduct of a thorough investigation identifying the core components of the superstructure and the main participants involved in the strategic planning and implementation of the Paramilitary Strategy, at least since the arrival of the Yarborough Mission in Colombia in 1962. There are already vast amounts of thoroughly documented information and testimony available, a detailed examination of which (in order to verify, refute, correct or expand upon the claims and findings in each instance) would provide a wealth of information that could inform the investigation, understanding and explanation of more recent and ongoing developments.

“With respect to the evidence of systematic collusion between the public security forces and paramilitaries, it is time: “to lift the smokescreen of official lies and identify the relationship between the military and the paramilitaries for what it is: a sophisticated mechanism sustained in part by years of military advisors, training, weapons and official silence on the part of the United States which has enabled the Colombian Armed Forces to wage a dirty war and the Colombian bureaucracy to deny its existence. The cost: many thousands of Colombians that have been killed, disappeared, wounded and terrorized…” (Vega Cantor, 2015)

As mentioned above and in the previous report, almost all of the major investigations that have been conducted up until now – whether pursuant to the regular criminal and judicial procedures or to the respective sui generis investigations, tribunals and proceedings that have been created over time – have had strict limitations imposed on their jurisdiction, functions and powers by the Government and the National Congress. Victims and civil society organizations have attempted to overcome the institutional, legal and social obstacles and pitfalls blocking their demands for thorough investigations and their efforts to obtain justice by initiating proceedings in other jurisdictions, including in some instances before the courts of other countries, the Pan-American courts and human rights commission, or the International Criminal Court. For example, the proceedings that have been invoked to try to hold the executives and owners of Chiquita Brands accountable have at different moments involved all of these options (unsuccessfully up to now), ultimately appealing to the International Criminal Court:

“What they (the victims and their legal representatives) are trying to do (by lodging a petition with the ICC) is ensure that the role of those executives in contributing to the commissioning of crimes against humanity is investigated…

Sebastian Escobar, a member of CAJAR, emphasized the open-ended investigations ‘without results’ in Colombia and the ‘lack of political will’ to extradite those possibly responsible. To this he added the ‘difficulties and inability’ of the State to investigate the 14 suspects. In part, because obtaining their extradition from the United States ‘is very difficult’ – a North American citizen has never been extradited to Colombia – and partly, due to the impossibility of obtaining declarations from the Colombian paramilitaries extradited to the United States, who are leaving prison having completed part of their sentence and are obtaining residency permits there.

Escobar also condemned the impunity that could exist for these crimes pursuant to the JEP war crimes tribunal [established pursuant to the Peace Accord with the FARC], due to the difficulty of proving that the financing of paramilitaries by banana producers is related to the armed conflict. This is because the legislation establishing the JEP specifically excludes civilians indirectly implicated in the conflict – ‘third parties’ – from the Tribunal’s jurisdiction, and also because in Colombia the financing of paramilitary organizations is deemed to be “an aggravated crime of conspiracy to commit an offence”, which is not within the jurisdiction of the JEP either.”

In terms of the methods used to strictly curtail the jurisdiction and powers of the JEP (which is still conducting hearings and investigations), a similar series of legal restrictions and technical devices were used by the National Congress to strictly prescribe and limit the role, investigative powers and jurisdiction of the sui generis tribunal proceedings established to hear and consider testimony from the members of the paramilitary groups that demobilized between 2003 and 2006 (the Justice and Peace Tribunal). In this respect the report mentioned above (Mesa Nacional de Guarantías, 2018) states:

“[The most recent initiatives of the Executive and the Congress with respect to paramilitary groups] appear more like a project to thwart the judicial processing of these groups and perpetuate the pseudo-confrontation that the State says it is maintaining against them. They appear to reflect a fear that these groups could be effectively de-activated and that they might begin to state the truth as to who have been the main financers, sponsors and beneficiaries of their actions…

[Moreover], the State Prosecutor still has not investigated the confessions made by senior paramilitary commanders to the Justice and Peace Tribunal providing evidence of the alliances and participation of more than 120 companies with the paramilitary structures, including Drummond, Chiquita Brands, Postobón, Ecopetrol, Termotasajero, the National Cattlemen’s Union, and businessmen, banana and cattle producers in Urabá who were identified as financing their crimes and supporting the expansion of paramilitary groups in the region.

The Justice and Peace process [related with the 2005 accord between the Colombian State and paramilitary groups] did not occupy itself with deepening the investigations in order to clarify the responsibility of the civilian ‘third parties’ and businessmen [that supported the paramilitary groups] due to the fact that its jurisdiction only provided it with faculties to judge the responsibility of the combatants and not of their financers, patrons and collaborators.

The tribunal ordered the certification of 15,921 findings and orders directing the ordinary justice system to open investigations into third parties implicated in financing or actively supporting and collaborating in the operations and activities conducted by the illegal armed groups, many of which involve the relations that developed between local and foreign companies and businessmen and the commanders of the paramilitary groups and fronts. According to the Prosecutor General of the Nation in response to a petition by the Colombian Commission of Jurists, up until August 2017 there were 16,116 certified findings and orders. Up to now there have been no significant advances in the investigation, prosecution and judgement of these actors…” (Mesa Nacional de Garantías, 2018)

Colombian President of the Special Jurisdiction of Peace (JEP), Eduardo Cifuentes Muñoz, speaks during a press conference in Bogotá, on August 10, 2021.

This dimension of the armed conflict underscores the primordial importance of the Colombian Government’s recent request to the UN Security Council to amend the Peace Accord in order to remove some of the technical restrictions on the jurisdiction and powers of the JEP created to investigate war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in the course of the armed conflict, whether by the various protagonists of and adherents to the Counter-Insurgency Doctrine and Paramilitary Strategy (the Colombian and US Governments and Armed Forces, contractors from Israel and the UK, paramilitary groups and private companies), the armed insurgent groups or others. Strengthening the jurisdiction, terms of reference and powers of the JEP would be a major advance in this respect.

Beyond acknowledging the existence and investigating the origins, historical development and devastating social impacts and consequences of the Paramilitary Strategy, another primordial task is re-asserting Colombian sovereignty and control over strategy military/ intelligence/ security functions and powers. The findings and determination of the Constitutional Court in 2010 mentioned above clearly demonstrates at first instance the extent to which the Colombian State’s sovereign functions and capabilities have been variously abdicated and subordinated to the strategic interests and objectives of the US in particular, or indiscriminately privatized and outsourced to an incoherent assortment of private companies, contractors and other largely unknown third parties.

In this context, a cohesive strategy to re-assert Colombia’s sovereignty and strengthen the country’s military and security posture and capabilities might include, for example:

- Ongoing evaluation and oversight of all foreign military/ intelligence personnel in the country by a committee comprising members of the National Congress, the Presidency, and a joint task force of the major public security agencies and experts.

- Annulling the extravagant, unconditional and open-ended granting of diplomatic immunities and privileges to all foreign military/ intelligence personnel and contractors pursuant to secretive agreements and contracts with the US, Israel and the UK.

- Establishing as a pre-requisite to and condition of all contracts and agreements that all relevant equipment and technology acquired from other countries must be on the basis of ‘turnkey projects’, where to the extent that foreign personnel and technicians are necessary this is to be on a temporary basis during which Colombian officials and public security agencies are to receive training so that they are capable of performing all relevant operational and maintenance tasks in the shortest time possible.

- That Colombian public security personnel and technical experts must always be present in installations operated by foreign agents and in the construction and maintenance of all associated facilities and equipment within Colombian territory, and that they must accompany foreign personnel during their performance of official tasks and operations.

Geographic, Institutional and Social Diversity and Variability

Notwithstanding the existence of a relatively constant and highly centralized system that has directed and managed the implementation of the Paramilitary Strategy since at least the 1960s, it is also important to note that the paramilitary phenomenon involves the convergence of a wide range of disparate groups and interests, among which there have often been serious disputes and conflicts both among themselves and with the State. For example:

The developments taking place in Magdalena Medio (related to the rapid expansion of paramilitary formations during the 1980s) were replicated, with minor variations, in other areas. For example, in the province of Magdalena where Hernán Giraldo and Adán Rojas, two tenant farmers from the Sierra who had arrived to the region after fleeing the devastation wrought during ‘la Violencia’, decided to commence an armed resistance against the extortion of the guerrillas. This resistance resulted in the formation of groups that received an increasing amount of support from large landowners, businessmen and politicians of the region as the kidnappings and extortion by the guerrillas increased.

The organizations of Magdalena and Magdalena Medio were steadily building new alliances and linkages to the extent that in 1986 Adán sent his son Rigoberto to the self-defence school of Magdalena Medio, where he received military training. (The 50 students of one of these paramilitary schools were recruited in the following manner: 20 from Magdalena Medio, chosen by Henry Pérez; 20 from Pacho, chosen by ‘El Mexicano’; 5 from the Plains, chosen by Victor Carranza, and 5 from Medellín, chosen by Pablo Escobar and Jorge Ochoa. The instructors, who had arrived from Israel, told the students that once they finished teaching the course, they had another mission in Costa Rica and Honduras to train Nicaraguan contras…”) By 1989, there was talk of the existence of paramilitary groups in Urabá, Meta, Pacho (Cundinamarca), Cimitarra (Magdalena Medio in the province of Santander), Puerto Berrio, Doradal, la Danta, Las Mercedes and Puerto Triunfo (Antioquia) and Puerto Pinzón (Boyacá).

Each of the participants in this network brought additional resources, connections and skills, but they also brought their own particular interests and objectives. Those that wanted to protect themselves from extortion; those that wanted to stop communism and win the war; those from the realms beyond civil society that wanted to protect their airstrips, laboratories and commerce; politicians, their patrons and voters. In Magdalena for example, the group of Rojas ended up offering amongst its ‘services’ persecution, threats, violent displacements of small land owners, and the assassination of trade unionists. The thread that brought them all together, despite their many differences, was a visceral hatred of the guerrillas, communists, and individuals and social and political movements that they stigmatized as ‘allies of the insurgent groups disguised as civilians’.

These networks, fluid in composition and which have been modified and reconstituted over time, nonetheless conserve some common characteristics. They articulate sectors of the military and the police, elected politicians, judges and cartels, no longer solely around the dispute for land, but above all in the pursuit of territorial control, to the extent that they have embarked upon a war for control over the constitution of social order at the local and regional level, in the sense that they have gone from disputing specific localities to governing them, at times extending their influence to the national level.” (María Emma Wills Obregón, 2015)

The same is of course also true in terms of the diversity, differences of opinion and disputes that exist within and between each of the various State institutions involved, as well as for the main armed insurgent groups – the FARC (prior to their demobilization, afterwards manifested by the creation of several distinct ‘dissident groups’ in different parts of the country) and the ELN – both of which comprise a multitude of (usually geographically-defined) fronts and columns operating in particular regions.

The objectives, actions and motives of the leadership and members of each regional front, and the overall tenor of their relations with local inhabitants, State institutions, the military units deployed in the region and others (local political/ economic leaders and factions, landowners, the illegal economy, other illegal armed groups, etc.) are substantially influenced by the attitudes of their senior commanders, the objective conditions in which they operate, and the degree of cohesion and discipline within each group, notwithstanding the formal structures and proclamations of the Central Command in each instance.

For example, some of the factors associated with the motives, activities and objectives of the illegal armed groups, and their relations with the communities where they operate (which in some cases could generally be characterized as a type of relatively benign coexistence, in others as pure terrorization and total territorial and social predation and control, while in many other instances relations vary between the two extremes), usually include: do the illegal armed groups have a stable and substantial core membership; are there personal or ideological disputes between individual commanders or sub-units; have most members been recruited from the areas where they operate, or have they in effect been recruited from other areas to invade and take control over adjacent territories?

In this sense, while it is usual to refer to ‘the armed conflict’, there are of course in reality innumerable conflicts occurring simultaneously at distinct levels and between various economic, social and political factions and groupings, from predominantly localized and limited characteristics, activities and belligerents in any given area to their constantly changing dynamics and interactions with regional, national and international or transnational dimensions, actors and interest groups.

Meanwhile, adding further tension and uncertainty to the relations between the current president and the leadership of the armed forces is the fact that in the 1980s Gustavo Petro was an active member of the M-19 guerrilla group. At one point he was captured by the security forces and held in a military prison prior to his trial, during which time he was reportedly subjected to a series of ‘enhanced interrogation’ sessions. He was released several years later after the M-19 signed a peace agreement with the Colombian Government and demobilized. The main political party formed by the former armed insurgent groups, Unión Patriótica (UP), immediately experienced what has been described as a ‘political genocide’ orchestrated from the highest levels of the Colombian State/ Establishment (actively assisted by their counterparts in the US and Israel in particular) during which over 4,000 UP members were assassinated, including sitting members of the National Congress, Governors, Mayors and several high-profile presidential candidates.