Written by Uriel Araujo, researcher with a focus on international and ethnic conflicts

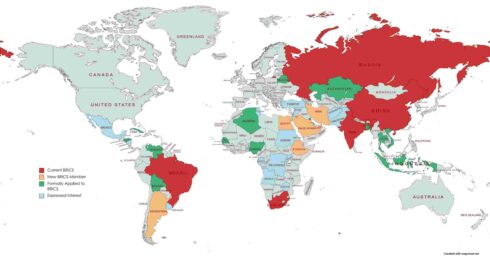

Even a cursory glance at the latest headlines can show that the Global South is in the spotlight – largely due to the fact that BRICS has been gaining traction in that part of the world. The recent BRICS Summit in Johannesburg, for instance, saw the inclusion of six states (Egypt, Argentina, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates) in BRICS, a grouping that now has 11 members, comprising nations from Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa. Prince Michael of Liechtenstein, founder of GIS Reports and of the Geopolitical Intelligence Services AG, remarks on how the African position has been experiencing newfound strength – even though historically the continent had been often viewed more as “geopolitical subject” than an “active participant” – something is now changing, and is seen in the current BRICS membership list as well.

Harsh Shringla, Chief Coordinator for India’s G20 Presidency, in turn, said, on September 4, that “even as global disparities persist, our commitment to prioritizing development, particularly in the Global South, which bears a disproportionate burden of the contemporary challenges, has been our guiding principle. In this regard, we have achieved substantial success.” India has discussed granting the African Union (AU) full membership in the G20. Shringla stated that, with 54 countries, and a $2.4 trillion combined GDP, “Africa holds tremendous potential for the future”. Under the ancient Sanskrit formula of “Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam” (“The World is one family”), New Delhi has been calling for global cooperation – with an emphasis on the South and on the complex task of building bridges between the political West and Russia.

Much has been written on BRICS, ranging from eulogies to rather skeptical analyses. Be as it may, it should be taken seriously and it cannot be ignored. In a clear response to the grouping’s enlargement, US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan announced on August 22, the very day the BRICS Summit began, that US President Joe Biden would call for reforms at the G20 Summit to ensure that both the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) better serve the needs of Global South nations. This has been met with some skepticism.

According to Adnan Akfirat, chairman of Turkish-Chinese Business Development and Friendship Association, the Johannesburg summit could leave a mark on history similar to the one which was left by the Bandung Conference in 1955. BRICS 11 collective population now comprises 3.5 billion people, which is about 40 percent of world’s population – in contrast to the 775 million people who live in the G7 nations. Even so, G7 still has an advantage in terms of GDP per capita.

One of the most notable BRICS proposals has been put on the table by Brazil, namely, establishing a BRICS currency – something which is also prioritized by both Moscow and Beijing, in face of today’s Western sanctions. Discussions are still ongoing and it remains unclear whether one should expect the emergence of a shared BRICS currency or rather a global reserve currency – for now, the latter seems slightly more likely in the short (or not so short) term. Either way, it would revolutionize the global system.

Challenging the dollar hegemony within the international monetary system is not an easy task. The value of any given currency, Prince Michael of Liechtenstein reminds us, has to do with the matters of both trust and liquidity, and the dollar is largely viewed today as the most liquid currency. However, trust on the dollar should decrease, as Washington has increasingly employed it as a weapon – the so-called “dollar bomb”, as I wrote before. The rising dollar, in fact, is bringing the world even closer to recession. John Kemp, senior market analyst and Reuters journalist, argues that the rapidly rising US interest rates have been among the main triggers of global financial instability for the last four decades, at least. Beyond the issue of the dollar, economic war-gaming in general is becoming a vulnerability for the US itself. De-dollarization will not come about overnight – but the process has been set in motion and, with the deteriorating US-Saudi relationship, the petrodollar itself might be at stake.

As I wrote, in June 2022, the rise in commodity prices was largely perceived in the Global South as a product of the West’s sanctions policy. This scenario forced emerging nations, increasingly alienated by the US-led West demands for alignment, to look for (extra) alternatives and for parallel, not necessarily rival, mechanisms. In this spirit, a new “non-aligned” tendency could be seen amongst African leaders, for instance. In the same manner, the BRICS grouping has had a window of opportunity to project itself as a kind of “alternative” to the Western bloc in an emerging multipolar world. And more and more nations are onboard.

The rise of Global South’s influence and its critique of Western power is driven, writes Sarang Shidore (Director of the Global South Program at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft), by realism – not “moralism”. BRICS is not necessarily a “rival” for G7 in terms of a Cold War mentality. The different nations that are joining the grouping have quite different interests and different views on the emerging polycentric world order – close as they may seem to be at times. Be as it may, the Global South is indeed “in the spotlight” – and this time not just as the stage for Great Power competition. Its great collective challenge is to navigate the new global framework, which is under construction, through non-alignment and multialignment. The declining US however, given its deep-rooted exceptionalism, does not seem to be ready to face this new reality. Overburdened and overextended as it is, it does not have much choice, though.